The Mid-18th Century Shift

The years leading up to the second siege of Louisbourg were some of the most tumultuous and uncertain that the island of Cape Breton had ever seen. Despite the apprehension, however, people living on the island were making plans for their future. In the 1750s, the French Governor, the Count de Raymond, ordered three roads to be built that would connect the main settlements of Cape Breton – Louisbourg, Port Dauphin (St Ann’s) and Port Toulouse (St Peter’s) – to the Bras d’Or Lakes and, therefore, to each other. In other parts of the island, like Baie des Espagnols (Sydney Harbour), people were coming to settle and put down permanent roots for the first time. Even the Bras d’Or Lakes, which had seen little to no European settlement in the early 18th century, were now getting attention. According to Sieur de la Roque’s 1752 census, a group of Acadians from mainland Nova Scotia had settled at Pointe la Jeunesse (today’s Grand Narrows) in the month of August 1751. This era, of course, came to an end when the island saw a significant depopulation after the fall of Louisbourg in 1758.

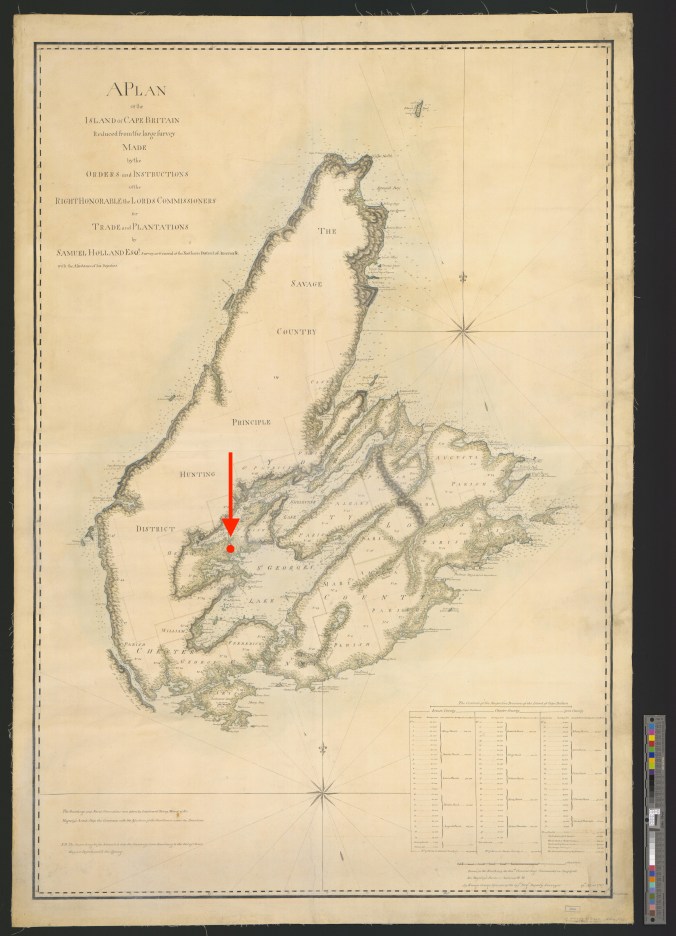

The Work of Samuel Holland

Jumping forward to 1765, Samuel Holland, Surveyor General of Québec and the Northern District of North America, arrived in Louisbourg. Seven years had passed since Louisbourg had fallen to the British, and apart from the destruction of Louisbourg’s walls, little had changed on the island. Holland and his team began a systematic survey of every cove, beach and harbour from Cape North to Isle Madame for the Board of Trade, the government entity that oversaw Great Britain’s colonies. Holland’s full description of Cape Breton Island was published in 1935 by archivist D.C. Harvey, and a corresponding map drawn by George Sproule, one of Holland’s deputy surveyors, can be found in the University of Michigan Library. By using both Holland’s description and Sproule’s map, we can successfully trace Holland and his team’s footsteps from one corner of the island to the other.

Holland’s survey portrays an island frozen in time, the clock having stopped in July of 1758 when Louisbourg surrendered to the British. In former centres of activity like Port Dauphin and Saint Esprit (St Ann’s and St Esprit respectively), abandoned and decaying houses were frequently documented by Holland and his team. Holland also notes that the fruit trees, once cultivated by the old inhabitants, were now growing wild and the lands they had cleared were slowly being reclaimed by nature.

Locating the Lost Village

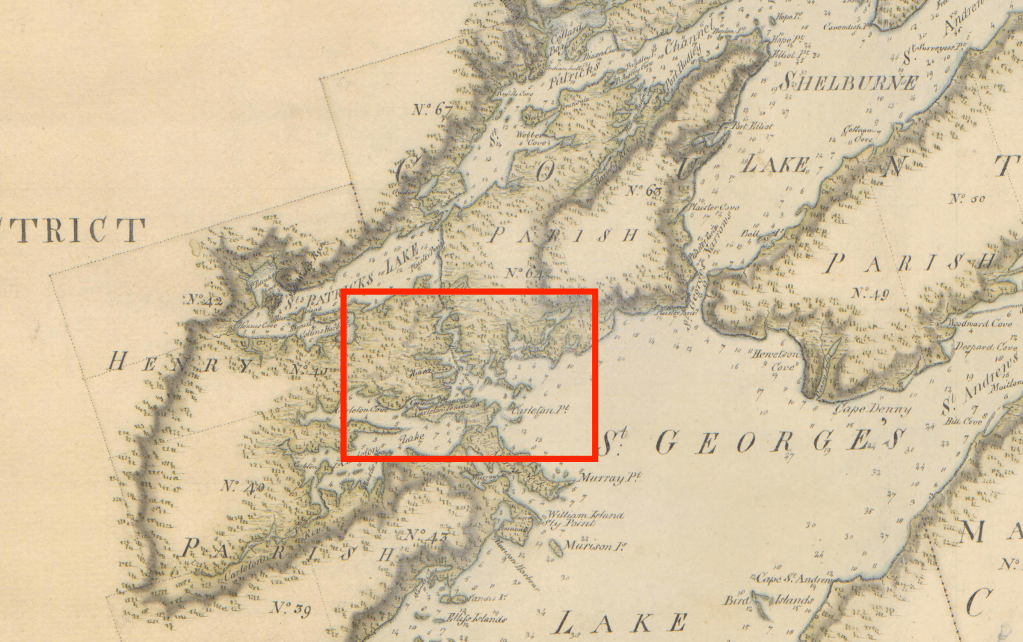

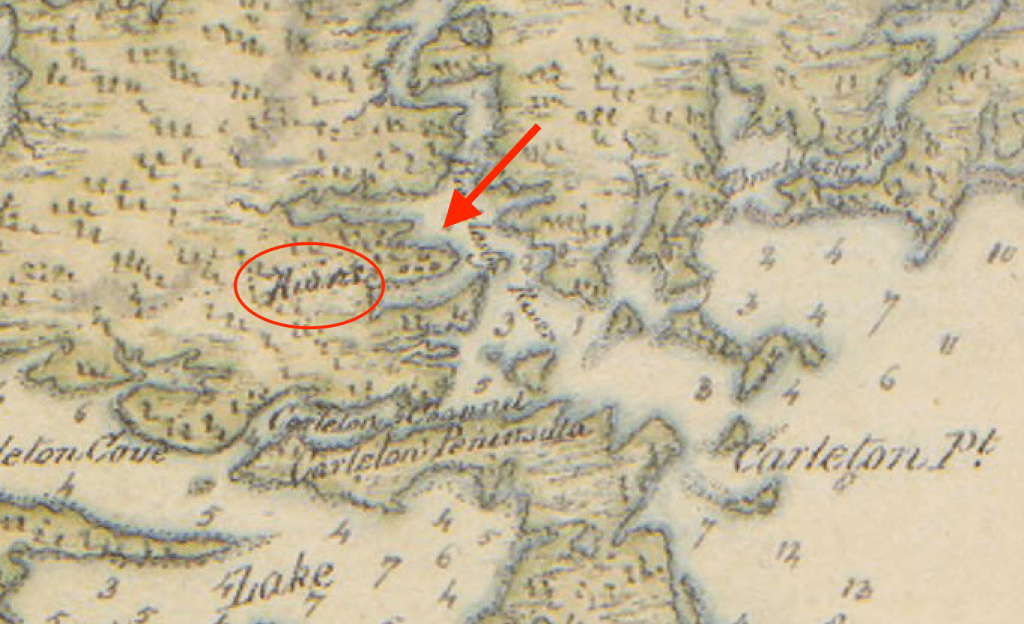

In order to complete the survey of Cape Breton Island, Holland assigned some of his deputy surveyors the enormous task of surveying the lands around the Bras d’Or Lakes – an area that the British knew next to nothing about. Interestingly, while surveying at Pointe la Jeunesse, the team apparently found no indications of the Acadian settlement described by La Roque in 1752. La Roque had noted, however, that the Acadians there were not satisfied with the land, and were looking to move somewhere else in the near future. As the surveyors continued some twenty kilometres deeper into the Bras d’Or, the following surprising entry is made in a location dubbed “Brocklesby River” and “Brocklesby Inlet”:

“Coast From the Narrows to Brocklesby Inlet … This River is navigable for Boats & Shallops to its Head, where there is an Indian Carrying Place into St. Patrick’s Lake; at one of the Coves on the West Side of this River, are the remains of a French Village, where there hath been a small Quantity of Cleared Land, but is now overgrown with Brush.” Holland’s Description of Cape Breton Island, p.70 – 71

No further information is provided by Holland about when this village was settled, who it was that had settled in this area, or what the name of this village was, if there ever was one. Coincidently, though, an entry in the journal of John Montresor, a British engineer who was stationed in Louisbourg in 1759, makes these intriguing remarks:

“1759 March 27th – One Officer – 26 Rangers, 3 private me of ye 45th Regt and volunteers, the whole consisting of 40 men, were detached from ye Garrison, by order of his Excellency Brigr Genl Whitemore, Govr of Louisbourg & to proceed on an Inland Scout, directing to Lake La Brador, from thence to Pointe la Jeunesse, a point of land so called from the name of a man, that settled there, one Le Jeune. So to cross the Lake again to La Badick bearing N from thence, where there is a straggling settlement, near the Saw Mill River, to bring in what French (Acadians) we could find inhabiting those parts.” John Montresor (parentheses his), the Montresor Journals, p. 188

With Holland’s description and Sproule’s reduced map of Cape Breton, we can identify Brocklesby River as the inlet of the Bras d’Or Lakes into which Portage Creek empties. This unnamed, obscure and extremely isolated French or Acadian village seems to have been in the area known today as Alba Station, on the Orangedale Iona Road (see image 1.1).

Unanswered Questions

With this information, we can come to a few conclusions. Given the geographic similarities, it seems likely that the “French Village” identified by Holland’s team and this “straggling (Acadian) settlement” mentioned by Montresor are one and the same. The fact that this “village” existed as early as March 1759 points to it being settled at an even earlier date. Finally, if Montresor’s information is correct, then it seems that this “village” was the second Acadian settlement on the Bras d’Or Lakes during the 18th century, and likely the only European settlement found on the lake’s shores at the time of Louisbourg’s capture in 1758.

There are, however, some unanswered questions. Was this where the Acadians from Pointe la Jeunesse eventually decided to settle? Did this isolated settlement have a name? How many people lived in this “village”?

Despite French engineer Grillot de Poilly having travelled through this very area (known to Poilly as Merigoeche but on French maps identified as Mirmiliguesche) in February or March of 1757, he makes no mention of this community. Perhaps it simply did not exist at that time. In fact, when Poilly travels through the Bras d’Or Lakes, there is no European settlement at all except a saw mill and a house located in the vicinity of modern-day Baddeck and the Catholic mission at Ste Famille (today’s Chapel Island).

Time will tell if more information about this settlement will come to light. However, it serves as a reminder that our understanding of history is always changing. In the words of Faulkner, “The past is never dead. It’s not even the past.”

Mr. Bourgeois;

I enjoyed the March article about the lost village in the Orangedale area. I was told just lately by a lady from that area that one can see the outline of a canal joining the two lakes just along the road that runs to the Little Narrows ferry. I will see if I can find a bit more information about it. You may already have that information. J. Coffey.

LikeLike

Thanks! Would love to hear if you uncover anything else

JM

The Lost World of Cape Breton Island

LikeLike