While I was knee-deep in research for the article “The Lost Settlements of 18th Century Cape Breton Island,” which explored the history of four 18th century communities whose exact locations are not fully known today, I would come across the stories of the people who put down roots in the very same areas in the decades following the end of French rule in Cape Breton – namely, the Gaels. I came to realize that examples of lost communities could be found not only in 18th century Cape Breton, but in 19th century Cape Breton as well. Considering the amount of research done on this era, I felt we would be remiss if we didn’t carry this brief analysis of lost communities into the century that shaped Cape Breton into the place we recognize today. We’ll look at three examples of communities that had their start in the early 1800s that no longer exist – the Old French Road, Clarke’s Road and Pollett’s Cove.

A warning: this is by no means an exhaustive list of communities that were settled in the early 19th century that have since disappeared. Also, unlike the four 18th century communities that were examined previously, the locations of the communities we will now discuss are all known, and so when this article refers to “lost settlements,” we’re referring to the fact that they simply don’t exist today as opposed to the lack of a precise location.

The reasons why these three communities have disappeared from Cape Breton’s landscape is not as easily summed up as their 18th century counterparts. French communities like St. Esprit, Allemands, Rouillé and Espagnole disappeared the century prior primarily because of war or poor choice of location. However, the differences between 18th century Cape Breton Island and the Cape Breton Island of the early 19th century could not be more pronounced. For example: the island’s administration, that administration’s policy towards granting land, the motive for settling in Cape Breton, what kind of land would be chosen by settlers and the economic conditions would all change between the time of Louisbourg in the first half of the 18th century and the arrival of the Gaels in the early 19th – you could describe them as two entirely different islands. Therefore, many of the factors that affected 19th century communities like the Old French Road, Clarke’s Road and Pollett’s Cove would not have affected the communities that had already passed off the scene during or immediately after the fall of the French regime in Cape Breton.

Starting in the 19th century, the Gaels began arriving in Cape Breton en masse as a result of the Highland Clearances. Dr. D.C. Harvey, archivist at the Nova Scotia Archives explained – “All who took part in this heavy migration to Cape Breton, subsequent to the Napoleonic Wars, were victims of both the new economic policy of the Highlands and the energetic action of shipowners and their agents in the emigrant trade. Since the one concern of the new economic landlord was to get rid of his tenants as easily as possible, of the emigrant agent to get his fee of 12s per head, and of the shipowner to unload his cargo at the nearest and most convenient port, it is obvious that most of the immigrants to Cape Breton would be penniless on arrival, and that many of them would be landed wherever wind and wave had carried them, regardless of if there were officials there to receive them or, preferably, where there were not.”1

During the 19th century, the most sought after lands were on the shores of the Bras d’Or Lakes, shielded from the harsh climate that battered Cape Breton’s southeastern shores. The land on the Bras d’Or had, for the most part, never been plowed, save a small part of the area now known as Grand Narrows and a “straggling settlement”2 somewhere in the vicinity of Baddeck during the 1750s. By the mid-1820s, those prime lots had all been taken, leaving only unwanted land in hardly ideal locations3. These came to be known as “back lands,”4 and our three communities are located in these kinds of geographic locations.

The Old French Road

Often times this project refers to le grand chemin de Miré, or something along the lines of “The Great Mira Road” in English. Built by the French during the 1730s, the road linked the harbour of Louisbourg to the Mira River, ending at the shores of the Mira opposite present-day Salmon River and Two Rivers Wildlife Park. It served to connect the many property owners along the Mira River to the capital at Louisbourg. This was one of the better quality roads in the maritime region at the time, in fact British engineer John Montresor, who had already travelled extensively through North America by the time he was stationed in Cape Breton in 1758, described parts of it as “a pretty good road”5 when he walked it in its entirety while conducting an inland scout to the Bras d’Or Lakes. Although much of this road was sparsely populated at the time, the villages of Rouillé and Allemands are notable exceptions. The two villages were intentionally settled in order to provide grain for Louisbourg, but the poorly executed plan fizzled not long after its conception.

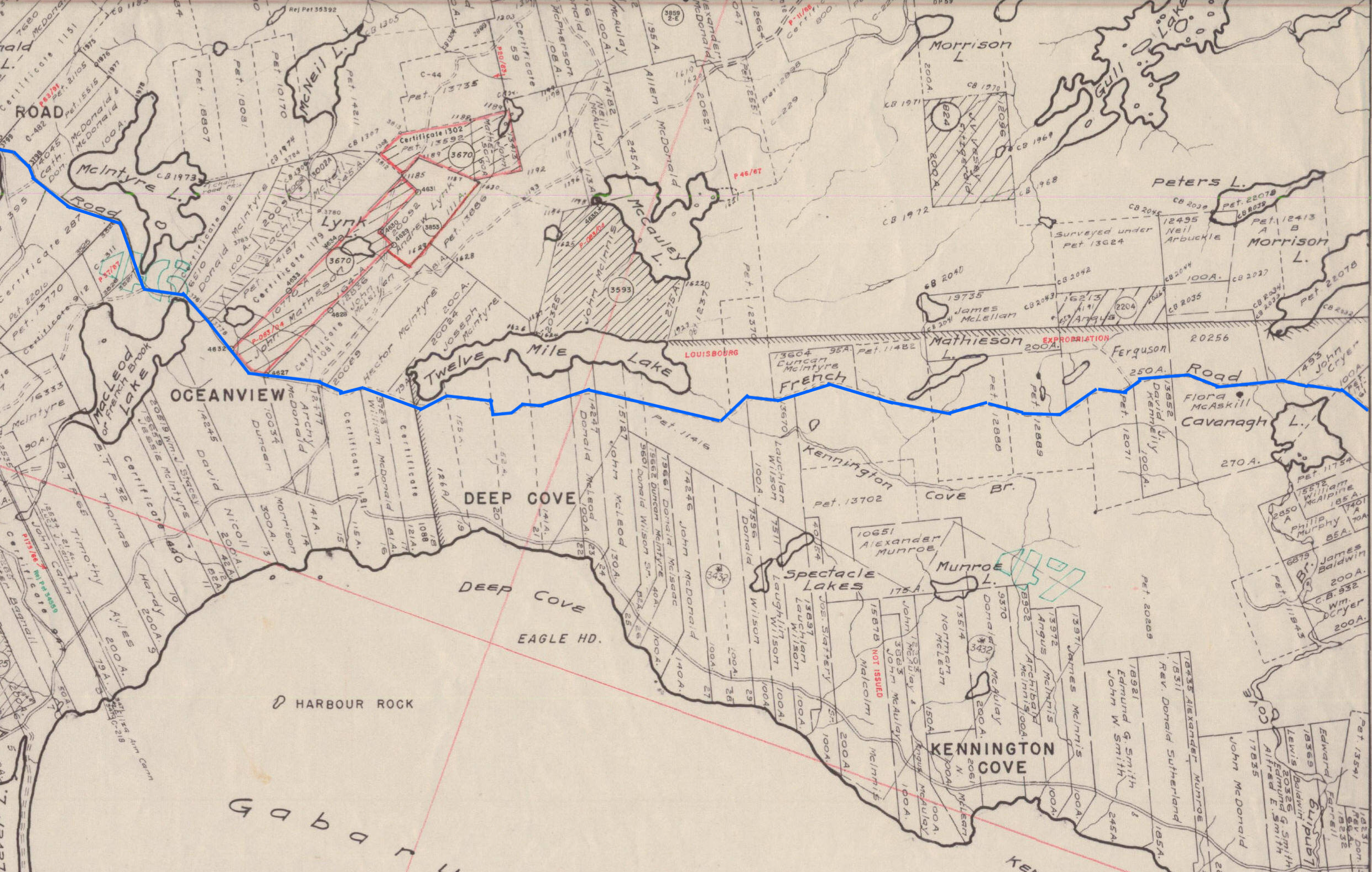

Despite the fall of the French regime in Cape Breton in 1758, the founding of the new capital at Spanish Bay in 1785 and the creation of a better road that served to connect the coastal communities in the Gabarus area, the grand chemin would survive as a secondary road also linking the communities in that part of the island. Eventually it became known as the “old French road.” Much of that road still exists today in the form of a backwoods trail that starts at the bottom of Park Services Road and comes out at Oceanview, where it then turns into the Gabarus Highway. Communities such as Oceanview, the aptly named French Road and Campbelldale developed along this part of the road, whereas homesteads and farms that developed on the part of the road that is now a trail have since disappeared.

An article written in 1922 by teacher and genealogist Michael D. Currie answers the question of when settlement on large portions of the Old French Road began: “The emigrants who came here (Cape Breton) from Scotland in 1832… settled in rear lots or “Back Lands”, as these localities were called, at East Bay, North and South, and also at French Road and elsewhere in Mira.”6 The Gaelic speaking settlers to this area of the road would’ve been those families who were not able to find land along the shores of the Bras d’Or and subsequently would have had to search for land wherever it could be found. It was no doubt the beginning of the predominantly Scottish flavour of the communities along the western part of the Old French Road (see figure 2.2).

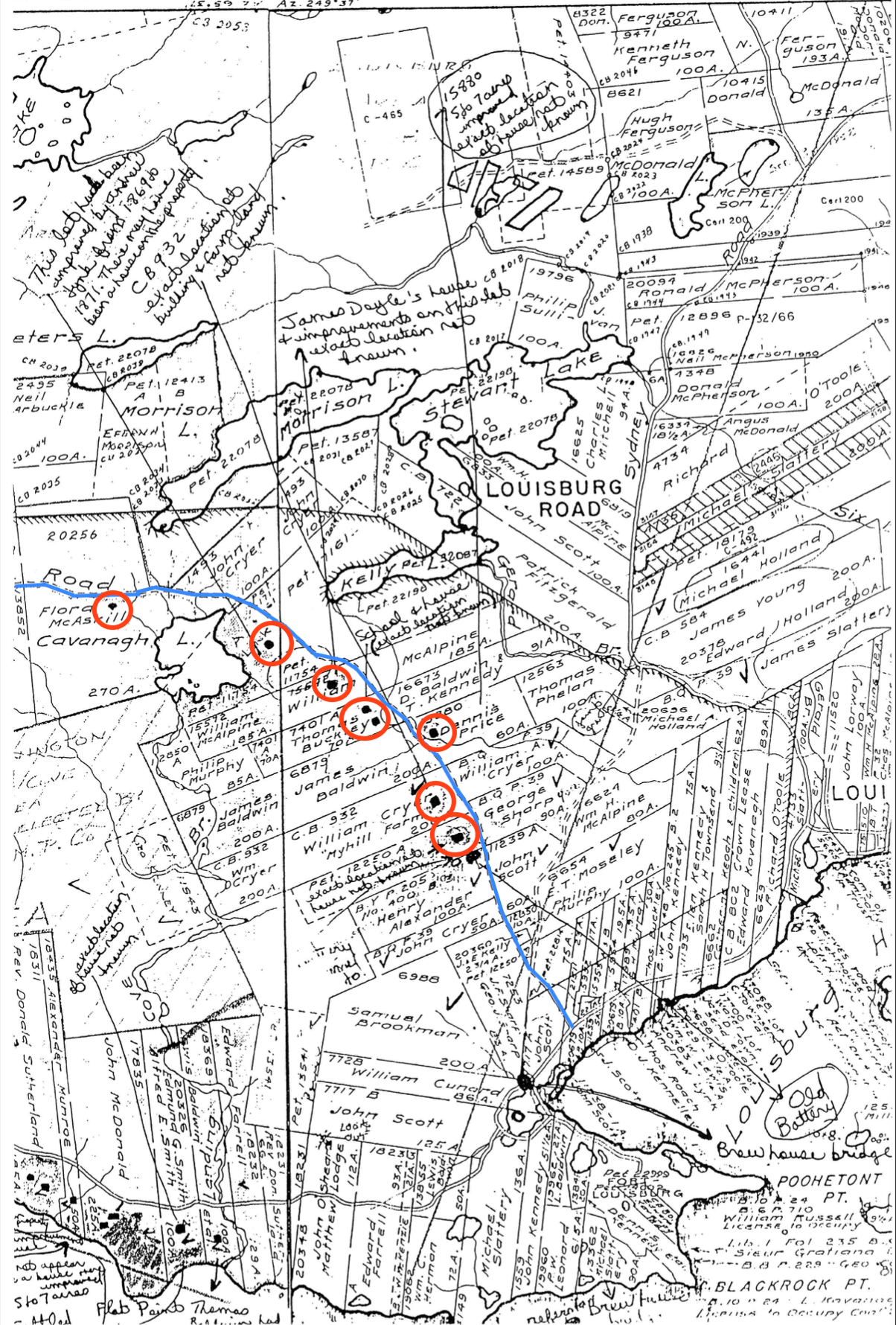

Before the arrival of Gaelic families further to the west, English and Irish families had settled down on the eastern part of the road nearer Louisbourg. The Crown Land Map index indicates families such as the Cryers, Kennedys, Buckleys and Prices had settled down in the vicinity of Kelly and Cavanagh Lake by the 1860s (see figure 2.1). The map even indicates the presence of a schoolhouse, but along with the eight or nine houses also identified on the map, no trace can be found today.

Much of the land which the Old French Road runs through was expropriated by Parks Canada in the 1960s for the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site, ending the possibility of further human activity within its boundaries.

Figure 2.1 – Crown Land Index Map #140 of the eastern coast of Cape Breton Island c. 1860 (From the Archaeological Resource Impact Study for the Fleur de Lis Trail) – land allotment and property owners along the Old French Road (marked in blue) in the vicinity of Louisbourg. For orientation, Louisbourg Harbour is in the bottom right. The map indicates that some eight or nine houses (circled in red) existed on the stretch of the road in the area that was once known as West Louisbourg. The marginal notes at the top of the map explain that the locations of all of these buildings are unknown today. Family names in this area are predominantly English and Irish.

Figure 2.2 – Crown Land Index Map #133 of the eastern coast of Cape Breton Island c. 1860 – a view of land allotment and property owners along the Old French Road (in blue) in the vicinity of Oceanview, Gabarus and French Road. During the 19th century, homesteads developed along its route as Scottish families moved into the Mira River valley. Family names in these areas include McIntyre, MacLellan, Ferguson, Morrison, McNeil and McDonald.

Figure 2.3 – The Great Mira Road c. 1735. This map housed at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France shows the same portion of the road as is shown in Figure 2.2. Property owners included Joseph Lartigue, judge (represented by the letter H) and a member of the d’Angeac family (Represented by the letter G). A few years before the fall of Cape Breton to the British in 1758, the villages of Rouillé and Allemands were settled in the upper left hand side of the map.

Clarke’s Road

Not long ago, someone reached out to me after having noticed the moniker “The Lost World of Cape Breton Island.” She inquired if I had ever come across a community known as “Clarke’s Road,” which was supposed to have been somewhere in the vicinity of Louisbourg but seemed to have disappeared with the passing of time. Despite having been born and raised 30 minutes away from Louisbourg in Sydney, I confessed that I had never heard of it. This individual explained to me that she even had school books from her grandmother who had attended the school in Clarke’s Road.

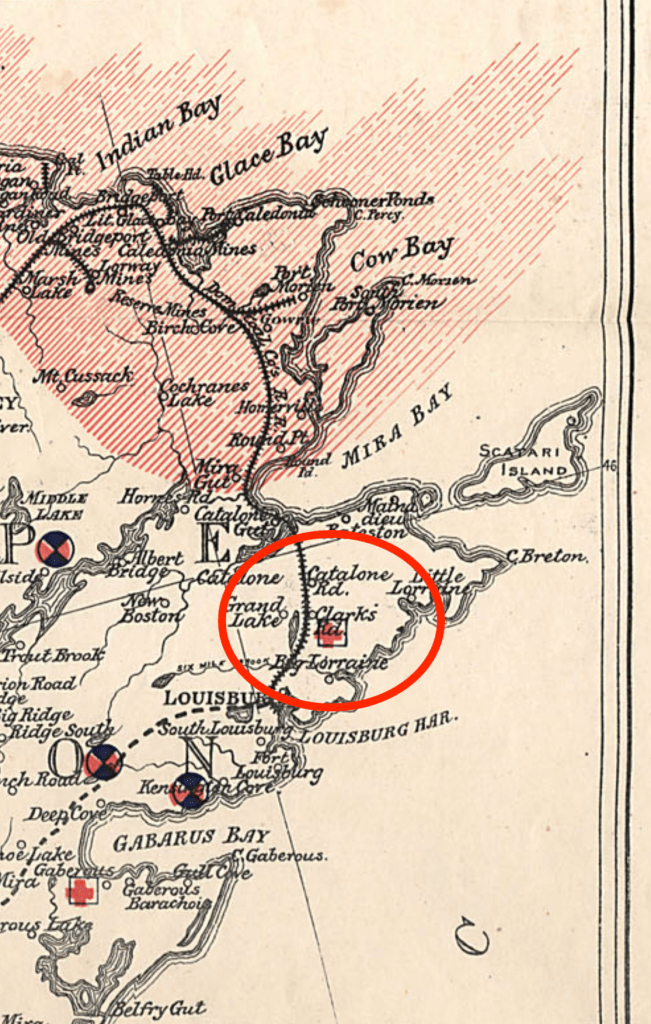

A bit of digging brought up that the actual road called Clarke’s Road had undergone a name change to MacCuish Road, but locals still knew the road by its original name7. Post routes from the early 1900s8 showed a Clarke’s Road somewhere between Louisbourg and Catalone Gut. Then I did a quick search for Clarke’s Road on Google Maps – I was shocked to find that, for some reason, Google Maps had the route of the old road clearly marked in its entirety from Route 22 all the way to Bateston on Mira Bay. Finally, I stumbled across a map in the Nova Scotia Archives that pinpointed the former location of the community of Clarke’s Road (see figure 3.1).

“After the Hector: The Scottish Pioneers of Nova Scotia and Cape Breton 1773 – 1852” gives us an idea as to when the first families arrived in the area around Clarke’s Road: “A staggering six hundred North Uist people and seven hundred Harris people had come to Cape Breton in 1828 … Some of the North Uist and Harris families went to Leitches Creek, in northeast Bras d’Or … Others settled along the Mira River valley, further to the east and at nearby Catalone.”9

I haven’t been able to find out anything else about this community. If I were to venture a guess, I would say that the community likely disappeared at the same time as the Sydney & Louisburg Railway, which according to the Halifax Chronicles Map of Cape Breton published in 1900, would’ve ran through or just beside the community of Clarke’s Road.

If anyone has more information on Clarke’s Road, I would love to hear more.

Pollett’s Cove

Cradled in a plain where two rivers empty into the Gulf of Saint-Lawrence sat the community of Pollett’s Cove. The geographic feature known as Pollett’s Cove is located about 15 kilometres up the coast from Pleasant Bay, and the community of the same name clung to the land between the ocean directly in front of it and the mountains of the Cape Breton Highlands immediately behind for nearly a century. The area around the old settlement is described as one of the most arresting views in all of Nova Scotia.

Pollett’s Cove was one of the main subjects of a talk delivered by Dr. Karly Kehoe of Saint Mary’s University in August 2021 entitled “Settlements and Legacies of Resilience in Northern Cape Breton” in Chéticamp, Nova Scotia. The larger theme that was developed by Dr. Kehoe was the effects of displacement, rural exclusion and past traumas on colonists arriving to Cape Breton and Nova Scotia during the early to mid 19th century, caused primarily by the Highland Clearances. It is an absolutely fascinating subject, and you can listen to that talk here.

The community of Pollett’s Cove was originally a squatter’s settlement, with the first Gaelic speaking people to inhabit the area arrived in the late 1830s10. Dr. Kehoe explained that Donald MacLean, the very first Gaelic settler to the cove, was from either Skye or one of the Uists.11 The other families that would arrive in Pollett’s Cove in the following years survived on a mixture of subsistence farming and fishing.

Throughout the 19th century, Pollett’s Cove was the home of many families – Mackillops, McLeans, Moores, MacKinnons and MacPhersons, the last of which left for good during the 1920s12. Nova Scotia photographer Clara Dennis passed through the area during the final moments of the settlement’s life and captured some of its last inhabitants on camera (see figures 4.2 and 4.3).

Dr. Karly Kehoe explained during her talk that she visited Pollett’s Cove during her research – a twenty-five kilometre hike through the gruelling terrain of the Cape Breton Highlands. Much of the landscape had changed after nearly a century of abandon. Still visible, however, were stone foundations, pieces of pottery, glass shards, and a pair of child’s shoes dating to the 19th century13. Over the decades much of the particulars of the settlement has been lost, such as the location of specific homesteads and graveyards that had at one point been known to the descendants of the Pollett’s Cove families.

In the same presentation, Dr. Kehoe summed up what the outcome was for this community after the last people left Pollett’s Cove for Pleasant Bay – “You go to Pleasant Bay and you talk to people, they have stories of Pollett’s Cove, they have relatives, they know people who are buried there – those communities never left them, even though people might not be living there right now.”14 It was a strikingly simple yet profound statement that points to the fact that even though the physical settlement might cease to exist, the community lives on through the stories passed on through the generations. That truth applies in a greater sense to the long lost communities along the Old French Road and Clarke’s Road as well.

How can we sum up this two part analysis of lost Cape Breton communities? Looking back at Dr. Kehoe’s statement – “these communities never left them, even though people might not be living there right now” – we’re provided with a kind of inverted framework in which to look at the lost communities of 18th century Cape Breton. Because of things like war and displacement at the end of the French regime in Cape Breton, many of those communities did not continue to live on past the end of the physical settlement. Despite this, the wealth of information that has survived from that time provides us as spectacular snapshot of the stories and events that took place in their communities at that time. And the settlements that have since passed off the scene from the 19th century continue to live in the collective memory of the communities alive today through the descendants of those who first settled those regions.

In the end, whether this project attempts to reconstruct those lost communities from the 18th century or retell the stories from their 19th century counterparts, there will always be more stories to tell from the history and the people that have called Cape Breton Island home over the centuries.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Harvey, D.C. – “Scottish Immigration to Cape Breton” – Dalhousie Review, Volume 21, Number 3, 1941, p. 1

- Scull, G. D. (Gideon Delaplaine) (1882). The Montresor Journals. p. 188

- Lucille H. Campey – “After the Hector: The Scottish Pioneers of Nova Scotia and Cape Breton 1773 – 1852” p.118, Natural Heritage Books

- Shears, Barry William – “Highland Minstrel to Tourist Icon: The Changing Role of the Highland Piper in Nova Scotia Society, 1773-1973” p.108, Library and Archives of Canada

- Scull, G. D. (Gideon Delaplaine) (1882). The Montresor Journals. p. 189

- Shears, Barry William – “Highland Minstrel to Tourist Icon: The Changing Role of the Highland Piper in Nova Scotia Society, 1773-1973” p.108, Library and Archives of Canada

- Eric Krause, 1996, “SANDRA FERGUSON’S CAPE BRETON CEMETERIES”, July 24 2022, http://www.krausehouse.ca/krause/SandraFergusonCBCemeteries/WillowGroveLouisbourg.htm

- Sessional Papers of the Dominion of Canada, Volume 10; Volume 27, Issue 10

- Lucille H. Campey, “After the Hector: The Scottish Pioneers of Nova Scotia and Cape Breton 1773 – 1852” p.121, Natural Heritage Books

- Clint Bruce (Host), October 21 2021, Season 1 Episode 4, “LAGNIAPPE: Dr. Karly Kehoe, Settlement and Legacies of Resilience in Northern Cape Breton”, Acadiversité Podcast, Université Sainte Anne, https://www.usainteanne.ca/creact/acadiversite

- Clint Bruce (Host), October 21 2021, Season 1 Episode 4, “LAGNIAPPE: Dr. Karly Kehoe, Settlement and Legacies of Resilience in Northern Cape Breton”, Acadiversité Podcast, Université Sainte Anne, https://www.usainteanne.ca/creact/acadiversite

- Clint Bruce (Host), October 21 2021, Season 1 Episode 4, “LAGNIAPPE: Dr. Karly Kehoe, Settlement and Legacies of Resilience in Northern Cape Breton”, Acadiversité Podcast, Université Sainte Anne, https://www.usainteanne.ca/creact/acadiversite

- Clint Bruce (Host), October 21 2021, Season 1 Episode 4, “LAGNIAPPE: Dr. Karly Kehoe, Settlement and Legacies of Resilience in Northern Cape Breton”, Acadiversité Podcast, Université Sainte Anne, https://www.usainteanne.ca/creact/acadiversite

- Clint Bruce (Host), October 21 2021, Season 1 Episode 4, “LAGNIAPPE: Dr. Karly Kehoe, Settlement and Legacies of Resilience in Northern Cape Breton”, Acadiversité Podcast, Université Sainte Anne, https://www.usainteanne.ca/creact/acadiversite

Clarks Road, my Grandmother , Mamie McRury, was born and raised in this village. She married my Grandfather Porter Wilcox of Little Lorraine, a few miles east of Clark’s Rd. on the coast, in the early 20th century. Her father died young of pneumonia returning from a shift at the coal pier in Louisbourg, leaving the children to work the farm. She would regularly recount stories of her life on the farm, one involved a forest fire in the area and the family covering the roof of their house with quilts soaked in milk .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing that very interesting information!

LikeLike

I am curious about the lost community of Gull Cove, and it’s interior, which is now, thankfully, preserved as the gorgeous Gull Cove Wilderness area. There seem to be remains hidden within that preserve that may well reflect settlements prior to the 1700’s. Those stories must be rich with history and knowledge.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The area of Gull Cove was known as Pointe aux Basques during the time of Louisbourg but saw the most activity during the 19th century. You can take a look at the Crown Lands Map index #133 which shows Gull Cove circa 1860 – https://novascotia.ca/natr/land/indexmaps/133.pdf. If the remains within the reserve are 17th century, Nicolas Denys mentioned in his description of Cape Breton that Olonnais (Likely from the French port Sables-d’Olonne) would winter at Louisbourg Harbour “formerly”, so there was at least some activity in that part of Cape Breton in the early to mid-17th century

LikeLike

My father John MacRury also was from Clarks Rd. He was the youngest in the family, although there was a baby after him that did not survive. His family moved to Louisbourg , not sure exactly what year but feel it was probably around 1920. Rev. Neil Maclean whose family lived there had a lot of information about the area, befor he passed away, he drew me a map of where everyone lived and I still have it somewhere but would have to search for it. If you wish you can call me and I will give you what info I have, phone number is 902 562 2128.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Although I am from Scotland I am well acquainted with the settlement of Clark’s or Clarke’s Road in Louisbourg, Cape Breton. I have come across it on many occassions from about 1843 and increasing frequency from around the 1880/1890s. The name then seems to disappear after 1912 but that does not necessarily mean it ended then.

The surname MacCuish is also familiar to me but I have never come across it as an alternative name for Clarke’s Road in over 20 years of genealogy research. Likewise, I have never encountered the settlement of Gull Cove mentioned by one contributor. Its location is clearly shown on the excellent map link you provided.

Two other contributors refer separately to a Mamie McRury and a John MacRury who happen to be siblings. Another MacRury (Malcolm) was the Postmaster at the South Louisbourg office from 1881 until it closed in 1893.

I hope that this is of some use to you. Although it is early days I imagine that you might be disappointed with the low response so far.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for that great info! It’s nice to finally have a rough start date for the Clarke’s Road community.

If I understand correctly, the name MacCuish is a recent addition (recent as in the last century) to a portion of the road closer to the vicinity of Louisbourg, so it makes sense that the name MacCuish doesn’t appear in any 19th century documentation. Someone local to the area might correct me on that, though.

I was wondering what sources you’re looking at that you were able to find that info about Clarke’s Road?

LikeLike

I am sorry that I can’t supply the source links that you asked for and appreciate that you can’t repeat information that is not fully validated. However, I am sure that other family tree compilers (Canadians ?) can confirm the potential Clarke’s Road timescales one way or another.

There is no need for a response.

LikeLike

Following my comments earlier today you should find the attached link interesting. It comes from the Nova Scotia Archives and suggests that Clarks Road was active from at least 1852-1920. It contains only births (7) and deaths (6) and looks like nobody got married there.

https://archives.novascotia.ca/vital-statistics/results/?First=&FirstS=&Last=&LastS=&Place=CLARKS&County=Cape+Breton&sYear=&eYear=&B=birth&M=marriage&D=death.

When searching it is important that you register the place as ‘Clarks’ only and it will bring up Clarks Rd and Clarks Road. Nothing comes up for ‘Clarkes’.

The site contains no original birth records prior to 1864. When they do appear they are delayed registrations. In the case of the 1852 birth date the registration did not take place until 1932.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Remarkable Stories From the Lost Settlements of 18th Century Cape Breton | The Lost World of Cape Breton Island