LAST UPDATED NOVEMBER 22 2025

A long forgotten homestead is slowly re-absorbed into nature – it’s a scene that people find both haunting and fascinating because it tells the story of something that has, ultimately, gone wrong. After all, no one builds a house for it to crumble only a few decades down the road. On a much larger scale, a community that ends up in the same state is even more unsettling, and if no one alive today has watched its slow decline into obscurity, it can be lost to the realms of history with no apparent connection to the present.

For centuries, Cape Breton Island has seen waves of settlers come ashore from many different parts of the world. The ebb and flow of peoples spurred on by the effects of war, by enterprise or by the simple desire to put food on their table has shaped the cultural fabric of the island for hundreds of years. Bretons, Normans and Basque arrived during the 18th century when the island was under the jurisdiction of New France, and then in the early 19th century the Gaelic speaking inhabitants of places like Barra and Uist put down permanent roots seeking refuge and a new beginning. As the tides of immigration and settlement came and went, communities likewise did the same.

What is meant when reference is made to ‘lost communities’ in this article? It refers to a settlement that no longer exists and whose exact location is now unknown. In some instances the community’s original name is still in use today, perhaps now referring to a general area instead of an exact location, while other times its original name has fallen into disuse or has been replaced entirely.

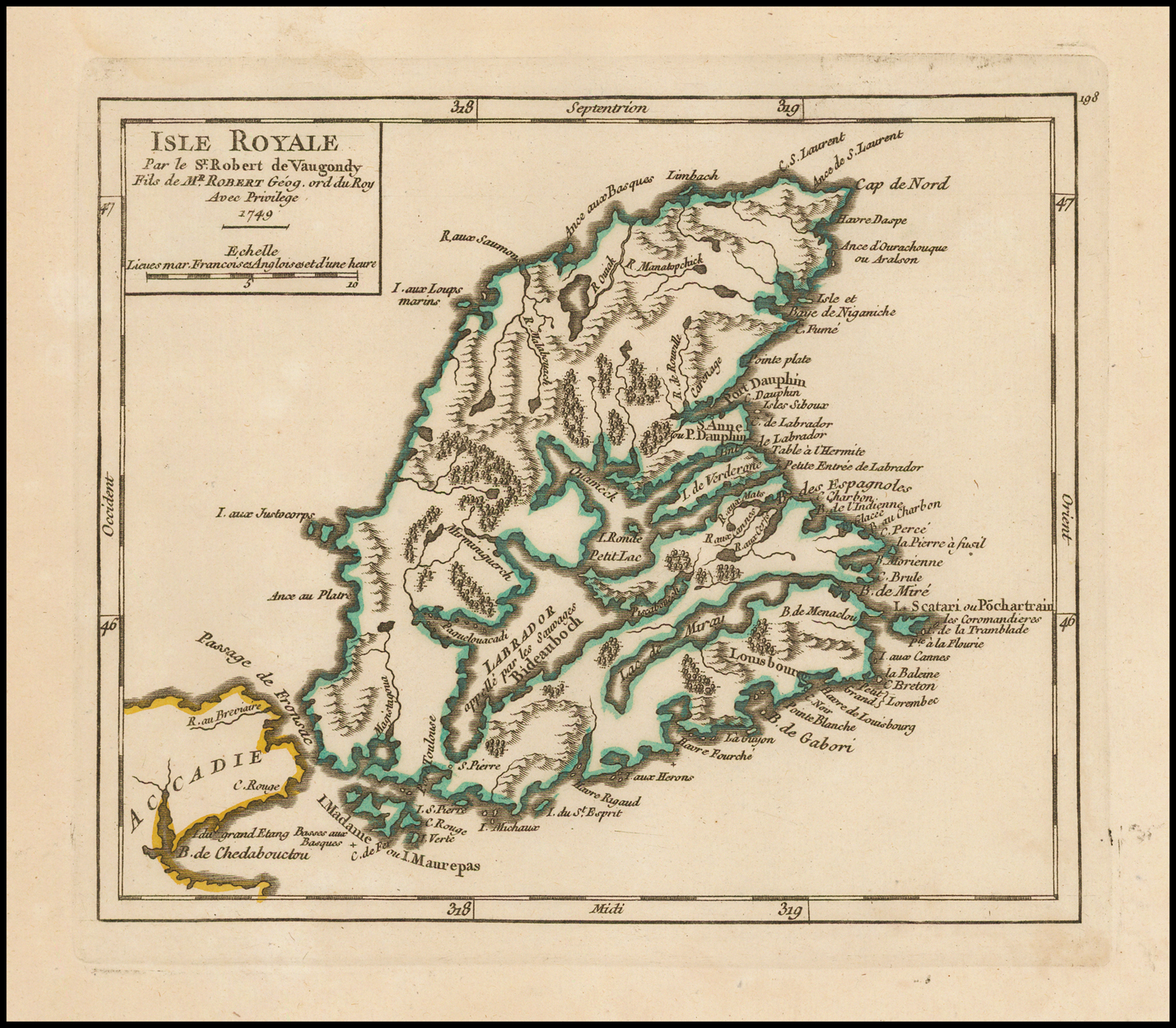

There are at least four prominent examples of these kinds of lost communities from 18th century Cape Breton Island, or Île Royale – the busy outport of St. Esprit, the soldier-village of Rouillé, Village des Allemands, and finally Espagnole.

To understand why the exact locations of these settlements were lost over time, an appreciation of how both the French and British used and understood Cape Breton Island is essential. The settlement dispersal pattern on Cape Breton Island during the 18th century is fundamentally different from the island’s settlement dispersal pattern of the early 19th century, simply because of the way French settlers and eventually British settlers set out to use the island. For the French, the ultimate goal of Île Royale was the cod fishery, so it was the Atlantic coastline that saw the most development. Although some French settlers did put down permanent roots during this period, many came temporarily either for the fishing season or because they were passing through this North Atlantic entrepôt on the hunt for better prospects. A handful of roads (some of them very well built) spread inland from the bustling harbour of Louisbourg, but they were few and far between. In fact, the inhabitants of Île Royale much preferred getting around the island by boat1. For the Gaels seeking refuge after the effects of the highland clearances during the 19th century, the aim was different. The goal for them was to find farmland and settle down permanently – nearly impossible on the coarse and rough shoreline that had seen the most activity only a century prior. So beginning in the early 1800s, attention was directed inland along the temperate shores of the Bras d’Or Lakes and the western part of the island, while the older roads and communities that had served the French so well only a few decades before slowly slipped into oblivion.

St. Esprit

NOTE: For more information on St. Esprit, listen to “Episode 5 – The Lost Harbour of St. Esprit” on The Lost World of Cape Breton Island Podcast.

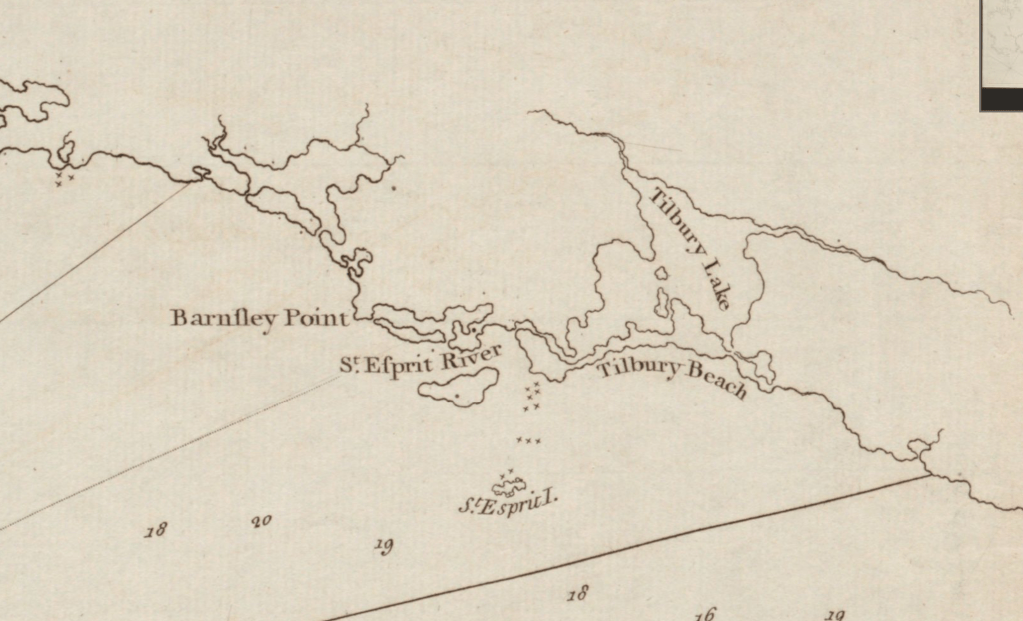

St. Esprit was one of the outports that developed after the French evacuated Placentia, Newfoundland in the year 1713. The community grew so quickly that, after only a few years, it became necessary for the colonial administration to appoint not only a harbour-master but also an intendant. The book Control and Order in French Colonial Louisbourg says about St. Esprit: “In 1734 there were 234 residents; three years later there were 546”2 – a significant settlement not only for Cape Breton, but also for North America in general at the time. During the 1745 attack on the fortress of Louisbourg, St. Esprit was targeted by two Massachusetts ships and burnt to the ground3. Sieur de La Roque, who conducted a census of Cape Breton Island once it had been returned to the French at the end of the war, recorded a population of about 75 people, but said “there was a much larger amount of chaloupes (fishing boats) here before the war than there is today.”4 It’s likely that the community suffered a similar fate six years later during the second siege of Louisbourg. A map of the south-east coast of the island prepared by surveyor Samuel Holland in the 1760s shows that, by that time, there were no houses nor property boundaries left to record. Today, the area retains its original name but is much more sparsely populated than the original settlement of three centuries ago. Hundreds of years of erosion has no doubt fundamentally altered the coastline of St. Esprit since La Roque’s visit, so understanding not only where the entrance to the roadstead5 was situated but also the exact location of the 18th century settlement is almost impossible.

Allemands and Rouillé

NOTE: For more information on St. Esprit, listen to “Episode 6 – Allemands and Rouillé: The Mira River’s Lost Settlements” on The Lost World of Cape Breton Island Podcast.

The villages of Allemands and Rouillé, settled in the early 1750s, have also been forgotten over the course of time – to some extent even more so than the busy harbour of St. Esprit. The area of the Mira River where these villages were located did not retain either of the names given to them by the French, and the villages’ exact location (along with the precise route of the Great Mira Road on which they were built) are also unknown to us today.

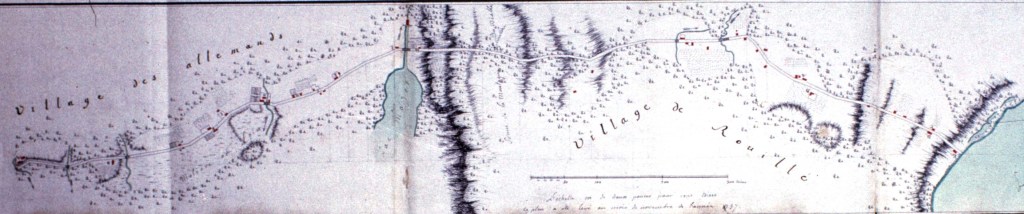

Village des Allemands was settled by a group of German immigrants from the Palatine and Ruhr6 regions of Germany, whereas Rouillé was inhabited by soldiers who married and were tasked with farming the land to provide the capital, Louisbourg, with grain7. Historian Margaret Fortier says: “By 1756 the outlook for the two villages was not bright…Most of the soldiers…were either aged or bad specimens drawn by the promise of three years free rations… Used to the lazy life of troops, he said, they preferred hunting to working the land.”8 John Montresor, a British engineer writing in 1759, tells us that this area was also known by the French as ‘les deserts,’ because the land had been entirely cleared of trees. Montresor took the Great Mira Road (see figure 3.0) on his way to the Bras d’Or Lakes and described passing through what remained of the two villages in his personal journal9. Likely, both villages were burnt down the year before during the second siege of Louisbourg.

Figure 3.0 (click to enlarge) – A 1757 map of the Great Mira Road (le grand chemin de Miré) in the vicinity of the Mira River. Village des Allemands and Rouillé are clearly marked, with houses indicated in red. The villages and this portion of the Great Mira Road no longer exist today, and their location and the route of the road remains unclear. The water on the far right side of the map is the Mira River. (Eric Krause – krausehouse.ca )

Espagnole

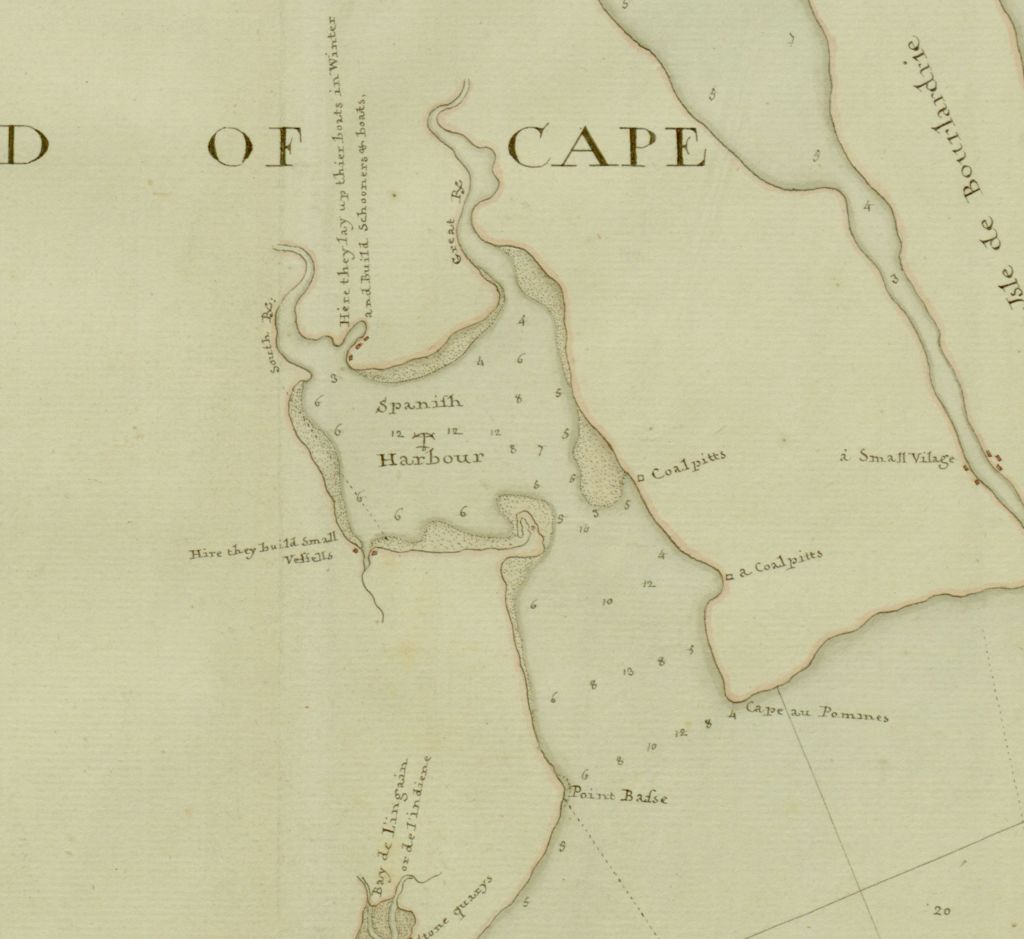

We learn about the community found at Baie des Espagnols (frequently abbreviated “Espagnole” by the people of Île Royale) from “Les Derniers Jours d’Acadie, 1748 – 1758”, by Gaston de Boscq de Beaumont. “Les Derniers Jours de l’Acadie, 1748 – 1758” is a compilation of letters that passed through the hands of Michel Balthazar Le Courtois de Surlaville, Major of the Louisbourg garrison during his brief stay in Île Royale following the re-occupation of the island by the French beginning 1749. From these letters we get a fleeting glimpse into the Île Royale social scene, along with some of the latest colonial gossip sprinkled with Surlaville’s dry and sarcastic personal commentary written in the margins. Espagnole was for the most part a community of Acadian habitant-labourers who lived in and around Baie des Espagnols after the return of the French to Île Royale in 174910. The governor of Île Royale, the Count de Raymond, also sent twenty-five soldiers to work the land, similar to the village of Rouillé out on the Mira11. Writing to the Secretary of the Navy in France, Raymond explained: “This harbour is perhaps one of the most beautiful ports in any French colony, and is already inhabited by a large number of Acadian families, from whom there are almost sixty girls ready to be married which, all of a sudden, will provide wives to our new colonists.” Baie des Espagnols is known today as Sydney Harbour.

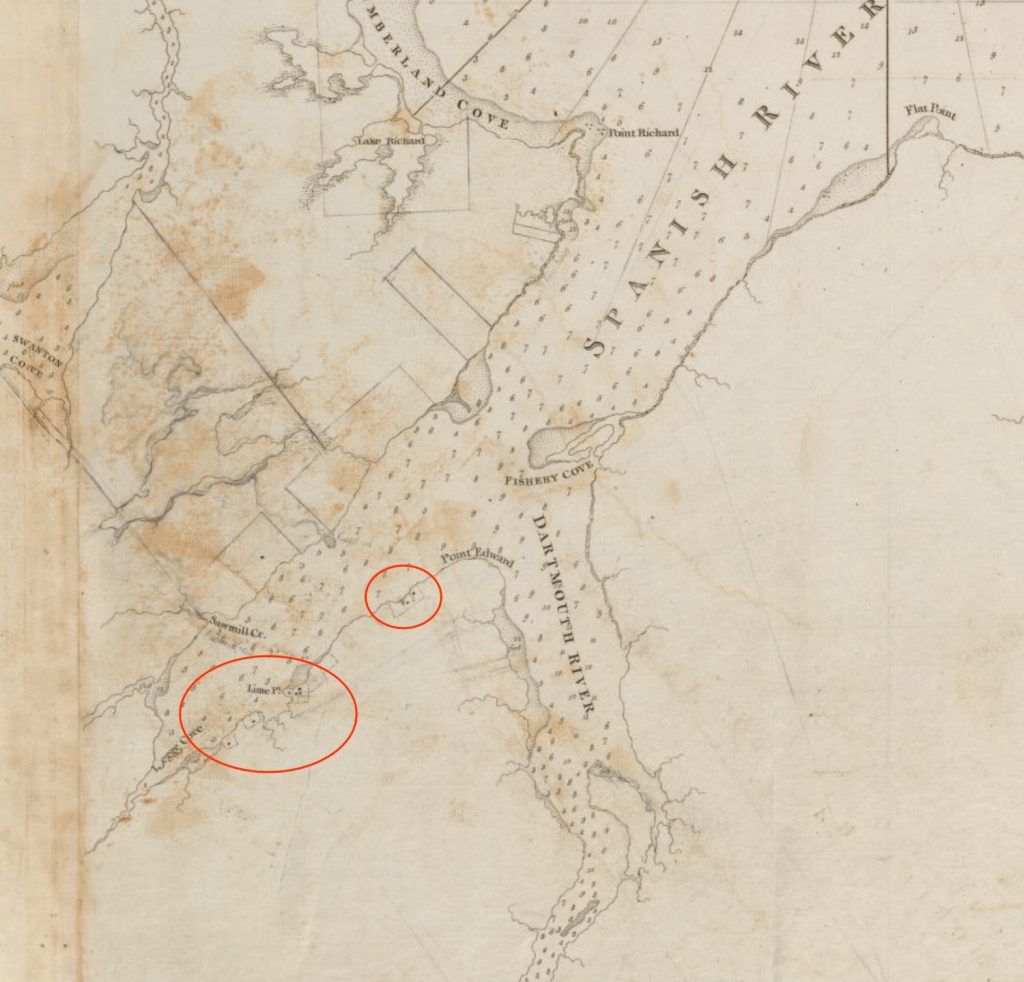

From Surlaville’s correspondence, we can learn quite a bit about the goings-on of this fledgling settlement. Again, the idea was for the settlement to produce grain so that the colony could become self-sufficient. Governor de Raymond in effect called the Acadians in Espagnole lazy12 for not producing any results. On the other hand, the Acadians tried to explain to him and other government officials that the land was not fit to farm. It’s mentioned in passing that around 1753 many of the Acadian families in Espagnole moved back to mainland Nova Scotia/Acadia, there to “exercise their laziness,”13 as one official put it. Likely, they returned to Nova Scotia/Acadia to suffer deportation a year or so later. A map of Baie des Espagnols from the 1760s or 1770s was included in J.F.W Des Barres’ “Atlantic Neptune,” a compilation of charts of the North American coastline assembled under the direction of the British Admiralty and published in 1777. The map shows a concentration of homes along the shores of the western arm of the harbour, and it’s possible that this was what was left of the Espagnole mentioned so often in correspondence from the period. There was also talk of a brickyard somewhere in the area14, and possibly a quarry15. After thirty years of abandon, work would begin at the bottom of Baie des Espagnols on the new capital of the Colony of Cape Breton Island, which was dubbed Sydney after the British Home Secretary. The colony’s first lieutenant-general was none other than J.F.W Des Barres, the creator of the “Atlantic Neptune.”

An event documented in Surlaville’s correspondence is the story of a French officer named the Chevalier de La Noue who fell in love with an Acadian shepherdess from Espagnole. He was denied permission from his superior officer to wed and so threatened to resign his commission in protest. He was finally able to marry her secretly before anyone had a chance to do anything about it16. Once the authorities found out, however, he was thrown in prison, sent back to France and forced to end the marriage, an event that highlights the rigid separation of classes that existed in French and European society at that time and that spilled over into colonies like Île Royale.

Sieur de la Roque also passed through Espagnole in the early months of 1752. A little gem buried in his census records is the mention of 110 year old Anne Josette La Jeune, born in Port Royal and at that time living with her son and his family in Espagnole17. If her age was documented correctly, she would have been born during the last years of Louis XIII’s reign around 1642, making her an eye-witness to Acadia when it was still a colony of France. Another brief glimpse into this lost community – “Jean Boutin, habitant-labourer, he is alone in a small house that his children helped him to build. He makes hand-barrows and other small things for his own amusement.”18

It can be a shock to realize that these four communities were not made up of one or two lone dwellings on some distant frontier – they were sizeable settlements located a stone’s throw from one of the busiest ports on the North American seaboard. With the tumultuous events that took place in Cape Breton during the mid-18th century, these once busy communities were wiped off the map. Now, the stories of these communities can only be passed on through the history books. “Why,” you may ask, “are these stories even worth telling?” Because those people, like those of us born and raised in Cape Breton today, also called this island “home.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- Du Boscq de Beaumont, G. (1899). Les derniers jours de l’Acadie, 1748-1758, p. 66. Paris : E. Lechevalier

- Johnston, Andrew John Bayly (2001). Control and Order in French Colonial Louisbourg, 1713-1758. East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press.

- Howard Millar Chapin, A.B., (1887-1940). New England Vessels in the Expedition Against Louisbourg, 1745

- 1752 Census of Île Royale, Sieur de La Roque, p. 21 -30 – https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c4582/25

- 1752 Census of Île Royale, Sieur de La Roque, p. 21 -30 – https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c4582/25

- Fortier, Margaret (1983). The Cultural Landscape of 18th Century Louisbourg – Miré Region – Rouillé and German Village

- Du Boscq de Beaumont, G. (1899). Les derniers jours de l’Acadie, 1748-1758, p. 64. Paris : E. Lechevalier

- Fortier, Margaret (1983). The Cultural Landscape of 18th Century Louisbourg – Miré Region – Rouillé and German Village

- Scull, G. D. (Gideon Delaplaine) (1882). The Montresor Journals. p. 277

- 1752 Census of Île Royale, Sieur de La Roque, p. 164 – 192 – https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c4582/168

- Du Boscq de Beaumont, G. (1899). Les derniers jours de l’Acadie, 1748-1758, p. 103, 104. Paris : E. Lechevalier

- Du Boscq de Beaumont, G. (1899). Les derniers jours de l’Acadie, 1748-1758, p. 104. Paris : E. Lechevalier

- Du Boscq de Beaumont, G. (1899). Les derniers jours de l’Acadie, 1748-1758, p. 122. Paris : E. Lechevalier

- Du Boscq de Beaumont, G. (1899). Les derniers jours de l’Acadie, 1748-1758, p. 77. Paris : E. Lechevalier

- Du Boscq de Beaumont, G. (1899). Les derniers jours de l’Acadie, 1748-1758, p. 122. Paris : E. Lechevalier

- Du Boscq de Beaumont, G. (1899). Les derniers jours de l’Acadie, 1748-1758, p. 112. Paris : E. Lechevalier

- 1752 Census of Île Royale, Sieur de La Roque, p. 170 – https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c4582/174

- 1752 Census of Île Royale, Sieur de La Roque, p. 172 – https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c4582/176

Pingback: The Lost Settlements of 19th Century Cape Breton Island – the Old French Road, Clarke’s Road and Pollett’s Cove | The Lost World of Cape Breton Island

I know where the settlement of St Esprit is located

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi there, I’d be interested in hearing any information you may have. You can reply here, or you can contact me at lostworldofcapebretonisland@gmail.com

LikeLike

I wonder if “French Village Lake” in Grand Mira South area is related to the villages of Rouilles/allemands. The lake is situated along the Mira River near modern-day French Road. I’m unsure the history of the area there or how the lake got that name, but it certainly sounds like a name that some english guys would give to a lake that is situated near some no-longer-relevant French villages… ie rouilles/allemands

If you align the map South-North instead of North-South and look at imagery for French Village Lake you can almost see a resemblance to the historical map above. It has to be oriented South-North if the shores of the Mira are on the right-hand side of that map, assuming the villages were on the East side of the Mira River.

I’m no historian or expert, and maps often weren’t the most accurate back then… This is purely speculation. But the article piqued my interest so I went looking around on google Earth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi there,

You’re correct, French Village Lake is related to that area – it used to be called “Lac à Majeur” by the French. The stream that ran out of the lake into the Mira seems to have been a kind of dividing line between the two villages, along with a certain “Montagne du Diable”.

I’ve always assumed the same thing, that some English or Scottish settlers arriving in the decades following their destruction dubbed the lake “French Village Lake”. I haven’t been able to find proof of that, so I never put it in writing, but it certainly makes sense to me.

LikeLike

additionally when I examine satellite imagery on Google Earth from July 2003, forested areas surrounding French Village Lake appear to be old pasture/farm land (in 2003 large, open-grown white spruce canopies are visible which is an indicator for old pasture/field lands). Those areas appear to have been cutover for timber since then from more modern satellite images.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Forgot to mention – our latest podcast episode dives deeper into the geography/history of that area than this particular article does. You might find it interesting 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: Remarkable Stories From the Lost Settlements of 18th Century Cape Breton | The Lost World of Cape Breton Island

I would love to see an update on the St Esprit’s settlement. My guess is the narrow channel now connecting the lake to to ocean was much bigger back then which allowed easier access to the ocean from the lake and the settlement was likely on St Espirts. A storm or hurricane likely drastically altered the channel to how it is now being much smaller and not really navigable by any boat.

LikeLike

I believe you are right. After putting this article together, I found a map created by Samuel Holland in the 1760s that depicted St Esprit fairly clearly. It shows a larger channel and also an area that’s labelled ‘ruins’. Here is the link to that map –

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/w/wcl1ic/x-8240/WCL008308?lasttype=boolean;lastview=reslist;resnum=702;size=50;sort=wcl1ic_id;start=701;subview=detail;view=entry;rgn1=wcl1ic_su;select1=phrase;q1=Brun+Guide.

LikeLike