(October 7, 2022 – Since the publishing of this article, historian Éva Guillorel from the University of Rennes in France has done significant research into the origins of “La Complainte de Louisbourg.” She has uncovered evidence that this Acadian folksong is based on an older French song written about one of the sieges of Philippsburg. Her findings were published in the Spring 2022 edition of the journal Acadiensis and updates some of the information found in the article below.)

In the spring of 1944, Canadian folklorist Helen Creighton arrived in Cape Breton Island on her ever expanding project to collect, document and preserve the traditional songs of Nova Scotia. With some recording equipment loaned to her by the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C, she began to catalogue the songs from the village of Chéticamp, an Acadian community that had been settled in the years following the Grand Dérangement of the 1750s and 60s.

On June 6 1944, she sat down with a man named Tom Doucet who sang for her some of his repertoire of Acadian ballads and milling songs that had never before been recorded – many of them already centuries old. Among the handful that he sang for her that day was an unnamed song that told the story of the first siege of Louisbourg almost two hundred years prior. A few things quickly became apparent about this particular piece. Firstly, the lyrics were incredibly detailed. Second, it included visual descriptions that could only been provided by an eyewitness, and lastly, it appeared to be known only by the Acadians from the region of Chéticamp1.

Below is the original recording and the lyrics to “La Complainte de Louisbourg” (the name given to this lament sometime after) sung by Tom Doucet and recorded by Helen Creighton on June 6 1944:

Stanza 1:

C’est-y toi noble empereur

Qui m’avait placé gouverneur

De Louisbourg, ville admirable

Qu’on croyait en sûreté,

On t’y croyait imprenable,

Mais tu n’as plus résister

Stanza 2:

Ça n’était pas manque de canons,

De poudre et d’ammunitions,

En garnison 20,000 hommes,

nous avions tant de secours,

Mais je voudrais savoir comme ont-ils pris

Philisbourg

Stanza 3:

Les Anglais, soir et matin,

Animés par leur Dauphin,

Nuit et jour dans leurs tranchées,

Creusions, écouler leurs eaux

20,000 hommes par leurs hardiesse,

ils l’avont pris à l’assault

Stanza 4:

J’ai fait une composition,

moi et toute ma garnison,

de sortir de nos …

(Les paroles deviennent incompréhensibles)

En déployant nos enceintes, quittant baggage

et argent

Stanza 5:

J’ai quitté cent-vingt canons,

vingt milliers de poudre et plomb,

Quinze mille quarts de farine,

et trent-deux mille boulets,

Les Anglais ont bien la mine qui faire la

guerre aux Français

Stanza 1: English translation

It was you, my emperor

That made me governor of

Louisbourg, the beautiful town

We thought was secure,

We thought it was impregnable,

But you couldn’t hold out any longer

Stanza 2:

It wasn’t a lack of guns,

powder or munitions,

A garrison of 20,000 men,

We had plenty of support,

So I’d like to know how they were able to take

Philisbourg?

Stanza 3:

The English, evening and morning,

Kept busy by their Dauphin,

Night and day in the trenches,

digging, draining off their water,

20,000 men by their boldness

Pressed the attack

Stanza 4:

I added a composition,

me and you, my garrison,

to leave our …

(lyrics become garbled)

Leaving our dwellings,

leaving baggage and money behind

Stanza 5:

I left behind 120 guns,

20,000 of powder and lead,

15,000 quarts of flour

and 32,000 bullets,

The English are radiant after the

war with the French

(A modern interpretation of “La Complainte de Louisbourg” was released by folk musicians Le Vent du Nord in February 2019. You can listen to it here – https://leventdunord.com/musique/)

Down the road, the words sung by Tom Doucet from Stanza 4 were clarified, changing the word composition to condition and the garbled lyrics to de sortir de nos chaumières, armes et tambour battant. These two small changes to stanza 4 confirmed that the song was written about the first siege of Louisbourg in 1745. How so? Because after surrendering Louisbourg in 1745, the French garrison was allowed to exit with the honours of war – armes et tambour battant – whereas after the siege of 1758, the French left Louisbourg as prisoners of war.

An examination of the entire set of lyrics brings up a few questions: Are they really the words of an eye-witness to the siege of Louisbourg? Are the lyrics historically accurate? And what exactly is the link between this song, Louisbourg and Chéticamp, which was settled some thirty years after Louisbourg’s reduction?

Unfortunately, as is the case with the vast majority of traditional songs, it’s difficult to know for certain its true origins – if they are ever uncovered at all. The medium of ear and mouth as opposed to that of pen and paper will inevitably degrade the original lyrics of a song over the course of time – as is the case with “La Complainte de Louisbourg”. Condition became composition, a garrison of two-thousand became vingt-mille hommes. It’s something that adds to the mystique of traditional songs, but will always leave a question mark where a researcher may wish to leave a period.

In this post, we’re going to evaluate Chéticamp’s “La Complainte de Louisbourg”‘s historical accuracy, then address its connection with Chéticamp in the next.

This particular version of “La Complainte de Louisbourg” takes the form of a back-and-forth between the former governor of Louisbourg Louis Du Pont Duchambon and the King of France, Louis XV, where, in stanza 1, Governor Duchambon has to break the news to the King that Louisbourg has fallen to the English. In stanza 2, Louis XV demands an explanation for the loss of the colony. Near the end of 1745, it seems that Duchambon was actually able to get a meeting with Versailles after returning to France from Cape Breton – whether or not it was ever with the King is unclear.

The first stanza gives us a clue as to when “La Complainte de Louisbourg” was composed. The use of the word empereur to address the King of France during the 18th century is an anachronism – like reading about a clock in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. King Louis XV never did hold the title of “emperor” and it’s highly unlikely that anyone would have used such a term even symbolically to speak about the King of France during the 18th century. Interestingly, his entire title was visible to the population of Louisbourg from a plaque found on the Frédéric Gate – “King of France and Navarre”, albeit in Latin. The use of the word empereur to address a French ruler suggests a date after 1804, 1804 being the year Napoléon I crowned himself Emperor of the French, making the title a household buzzword not only in La Francophonie but in homes across the world. Also worthy of note are the many songs about Napoléon that circulated through Acadian circles in the Maritimes during the first three decades of the 19th century2, confirmation that they were aware of what was transpiring across the Atlantic.

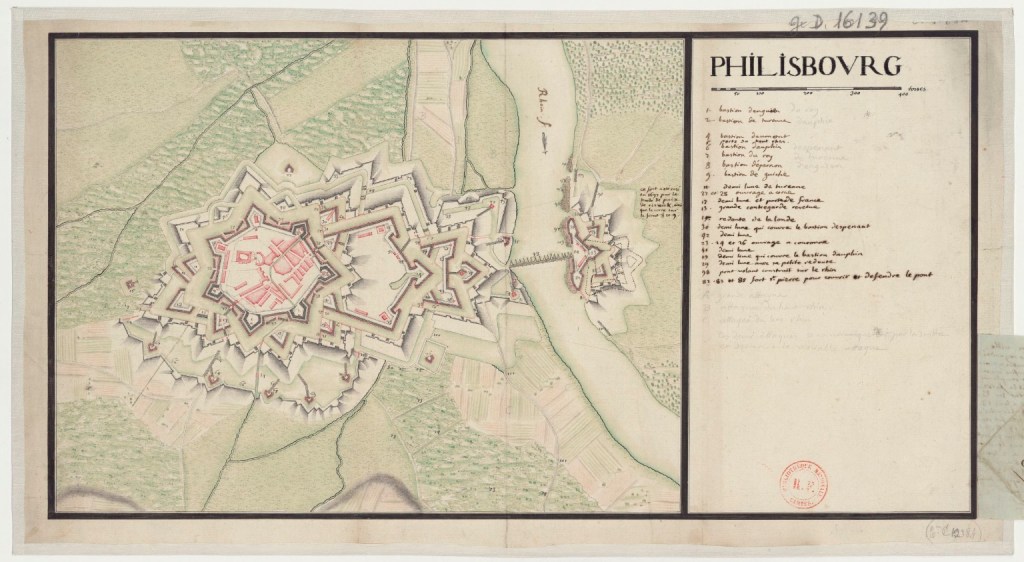

The reference in stanza 2 to Philisbourg is by far the most obscure reference in the entire song. Known to the French in the 18th century as “Philisbourg”, the fortress of Philippsburg sat at the frontier of France and Germany, and in 1734 was the location of a major siege conducted by the French against the Austrians during The War of Polish Succession. How could this place have found its way into a traditional Acadian song from Cape Breton? I’ve been unsuccessful in finding an exact link between the two. Any potential connection between Governor Duchambon and Philippsburg (which I thought was the most logical place to begin searching) is put to rest in historian Ægidius Fauteux’s paper “Les Du Ponts de l’Acadie”3 which fails to mention anything about this European fortress at all. However, a few similarities do exist between Louisbourg and Philippsburg. Firstly, Philippsburg was known for its crumbling fortifications and second its location was poorly chosen, much like Louisbourg4.

It’s in stanzas 3 and 5 that we see examples of the incredible detail that make the reader realize that they are listening to the words of an eye-witness. We read about the English “draining off their water” from their trenches, a detail not worth mentioning for many history books written about Louisbourg’s two sieges, but actually mentioned in the Lettre d’un Habitant de Louisbourg, published not long after the siege by an eye-witness to the events. The English are also “kept busy by the Dauphin”, or the Dauphin bastion, where the fiercest fighting took place between the clashing armies. Then we’re provided a list of Louisbourg’s provisions after the English had taken control of the town, including one thousands barrels of gunpowder. Near the end of the anonymous Lettre d’un habitant de Louisbourg, it makes a fascinating observation about how many barrels they actually had left: “What, above all, caused our decision [to capitulate] was the small quantity of powder we still had. I am able to affirm that we had not enough left for three charges…upon this it is sought to deceive the public who are ill-informed; it is desired to convince them that twenty thousand pounds still remain. Signal falsehood!”5 So it is quite possible that the civilian population believed that they had an ample amount of gunpowder left at the time of the town’s surrender.

Historically, “La Complainte de Louisbourg” holds up very well to what is known about Louisbourg during the spring of 1745. Despite the lyrics of this song having likely been composed during the early 19th century, the detail it contains does seem to point to an eye-witness source of information coming directly from Louisbourg and the old colony of Île Royale.

In the next post, we’ll discuss the connections between the village of Chéticamp and the fortress of Louisbourg that served as a basis for this lament.

______________________________________________________________________

1 It was also documented in Louisiana, but the song could be traced back to Chéticamp

2 Conrad Laforte, La catalogue de la chanson folklorique française, vol 6. Presses Université Laval, 1983 p. 409-423

3 Ægidius Fauteux, Les Du Ponts de l’Acadie. Bulletin des Recherches Historiques, August and September 1940

4 Interestingly, Poupet de la Boularderie, a veteran of the 1734 Siege of Philippsburg, was a prominent resident of Cape Breton and assisted in the preparations for the siege before being captured as a prisoner of war when the English landed at Gabarus and Pointe Platte. Perhaps this is the source of the comparison between Louisbourg and Philippsburg, but there is no evidence to suggest that this is the case.

5 George M. Wrong, M.A., Lettre d’un Habitant de Louisbourg, Warwick Bro’s & Rutter, 1897

Why would composition be emended to condition? Composition [agreement to surrender] is the right word.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi there,

According to Prof. Eva Guillorel in the article “La complainte de Louisbourg : chansons des sieges et circulation des cultures militaires entre Europe et Acadie a l’epoque coloniale” –

“the term most often used in the audio versions is that of “composition”, which takes up the meaning of “negotiation”… This linguistic archaism is removed or modified in the publications of the song in order to give the verse a clearer meaning for readers today.”

This is in regards to the word “composition” versus “condition.” I recommend referring to the above mentioned article, since it’s the most up to date information about this song and takes from sources on from both Acadie and France.

Cheers!

LikeLike

Since the singer clearly sings composition, and condition is also a different number of syllables, I’d recommend keeping composition in the French and putting “made a composition [surrender agreement]” in the English. “Added a condition”/”Fait un condition” doesn’t really make sense anyway. And by the way, “enceintes” refers to the walls of the fortress, not dwellings. Anyway, thanks for the post and thanks for answering.

LikeLike