English poet Edward Thomas once wrote: “much has been written of travel, far less of the road. It is a silent companion always ready for us, whether it is night or day, wet or fine, whether we are calm or desperate, well or sick.” Building on his words, it could be said that roads provide a kind of enduring backdrop to the common human experience. Roads can tell us more than simply how ancient people got from one place to another; they can tell us how they interpreted the landscapes they lived in and help us re-imagine the lives of those who once trod them.

Many such roads have come and gone on Cape Breton Island over the centuries. Some were large, while others were no more than footpaths. Some developed organically, while others were the project of ambitious colonial administrations. Some still exist, while others have disappeared completely. But each historic road played an important role – as Edward Thomas said, “a silent companion always ready for us”, or we could say for those who lived in Cape Breton some three centuries ago, now long gone. In this article we will explore three important roads that were built by the French in Cape Breton and also the smaller trails and footpaths that appear in 18th century documentation.

Cape Breton’s First Roads

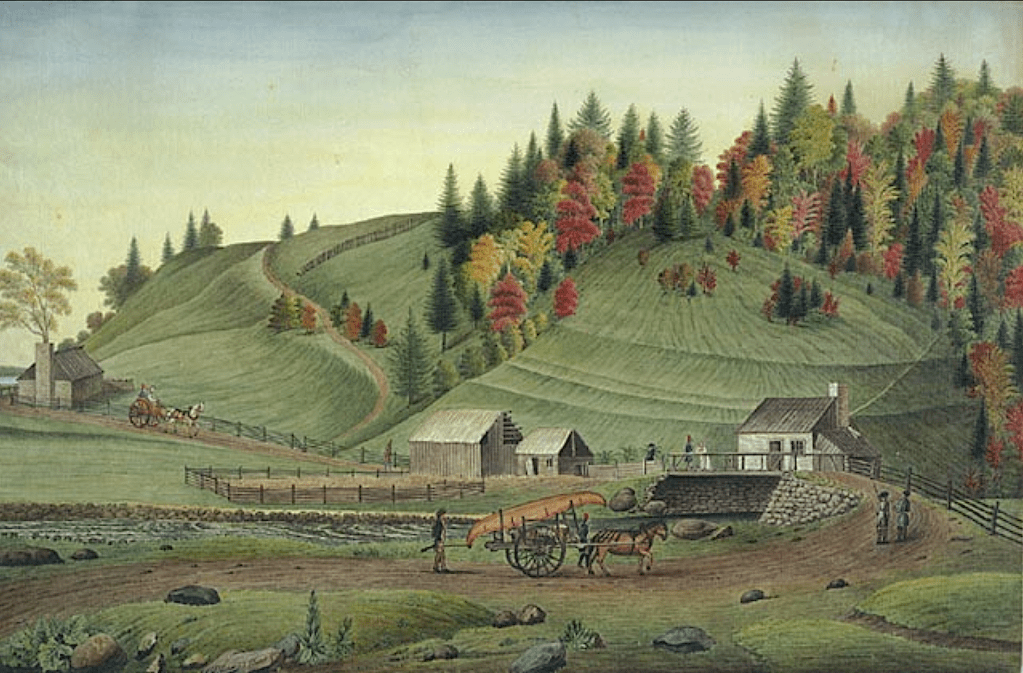

The first roads in Cape Breton were pathways created millenia ago by the Mi’kmaq that allowed them to get from one corner of the island to the other. These footpaths were called by the French “chemins plaqué”. Sieur Lartigue l’ainé explains what these “chemins plaqué” were in his 1758 map of Cape Breton Island (see Image 1.1). It says: “les lignes autrement dit les chemins ponctué en rouge désignent les chemins plaqué des sauvages par lesquels ils voyagent dans l’isle, ce ne sont à proprement parler, que des chemins tracés ou un homme a peine à passer.” Regardless of how practical they were or weren’t for Europeans, these paths were absolutely essential for anyone travelling into the unexplored interior of the island on foot.

Image 1.1 – “Carte de l’Isle Royalle en l’Amerique Septentrionale”, by Sieur Lartigue. The red lines crisscrossing the island are the “chemins plaqué” used by the Mi’kmaq and subsequently by French travellers. Courtesy Norman B. Levanthal Map Centre

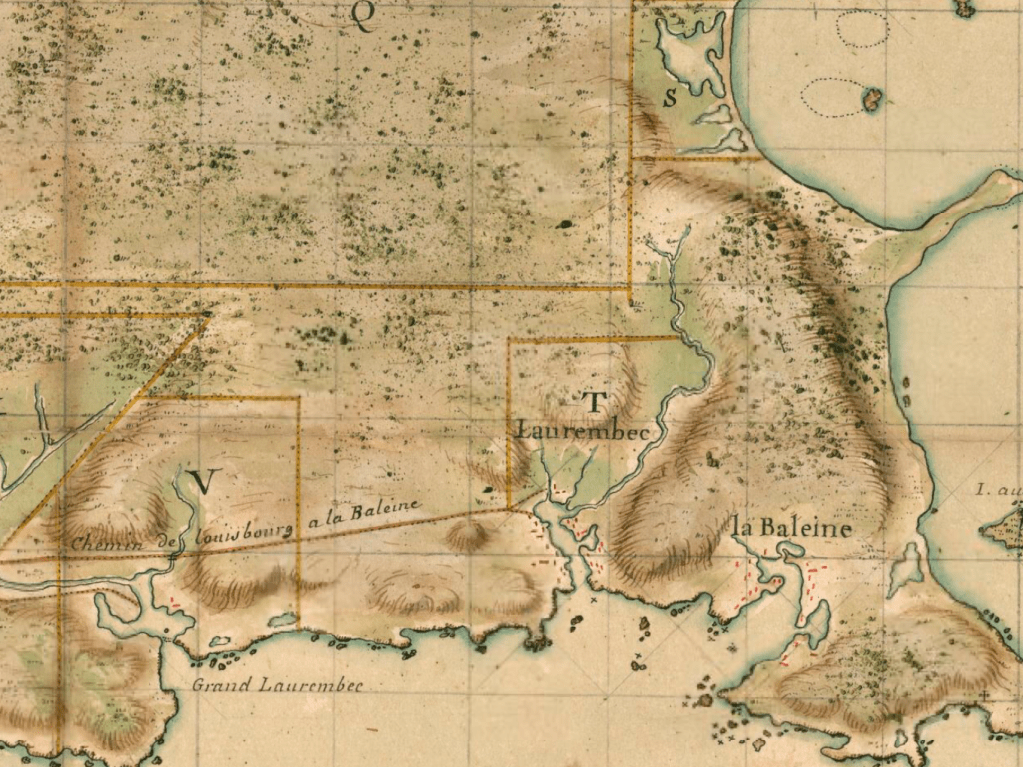

Image 1.2 – In this map, a “chemin plaqué” is indicated top centre, connecting the Great Mira Road to Devil’s Mountain (Montagne du Diable) overlooking Gabarus Bay. Courtesy BnF Gallica

It was Nicolas Denys in the mid-1600s who built what was likely the first European style road in Cape Breton. It was, according to Denys, a portage road from St. Peters to the Bras d’Or Lakes. He wrote in his work “Description Géographique et Historique des Costes de l’Amérique Septentrionale,” “J’ay fait faire un chemin dans cette espace (St. Peters, Cape Breton) pour faire passer a force de bras des chalouppes d’une mer à l’autre & pour éviter le circuit qu’il faudroit faire par mer.” A similar portage road was again built in this location about a century later in the early 1750s1, demonstrating the importance of this geographic area to the French. Today, the St. Peters Canal preserves these roads’ legacies by allowing maritime traffic to quickly access or exit the Bras d’Or Lakes.

The 18th Century

Some 70 years would elapse before more road building would ever be envisioned. With the loss of Acadia to the British and the evacuation of Placentia, Newfoundland in 1713, Cape Breton Island became the focus of France’s ambitions in the Maritime region2. After a few years of deliberation, the colonial administration decided that Louisbourg (formerly l’Havre a l’Anglois) would serve as the capital of the new colony3. In the decades to follow, settlements would spring up across the eastern coast of Cape Breton, and not long after, roads would reach towards these settlements starting from Louisbourg harbour.

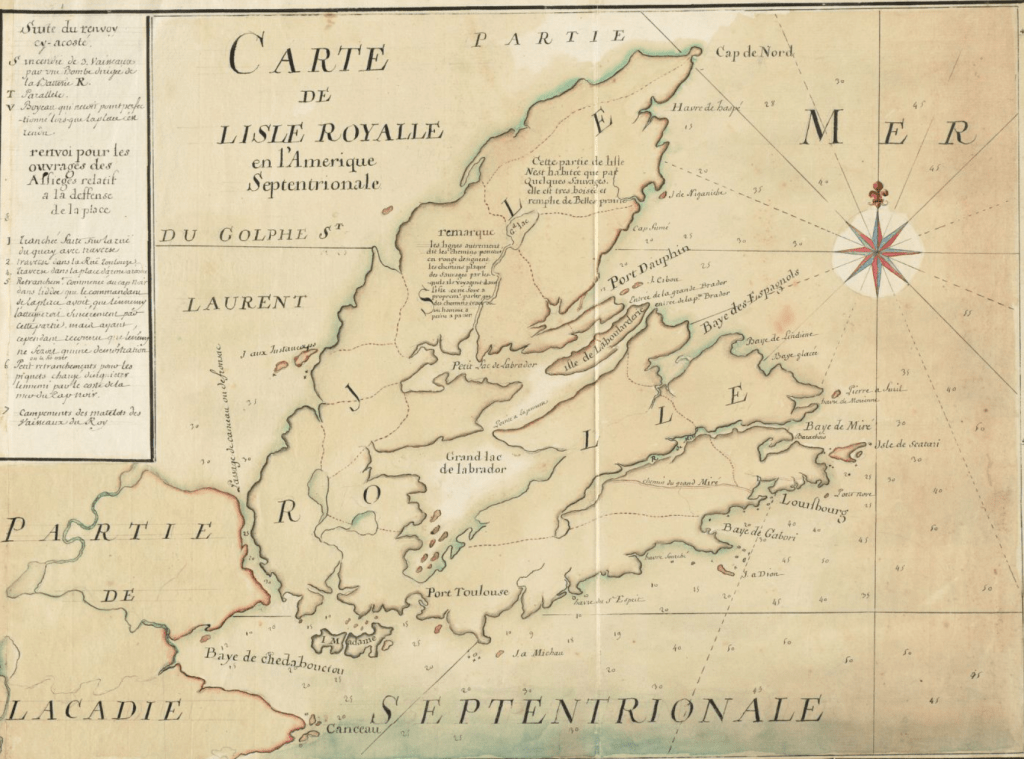

Image 2.1 – A map of the “Chemin Royale de Miré” ( the same as the “grand chemin de Miré”) dated 1723, the year construction on the road began. Courtesy BnF Gallica

The Grand Chemin de Miré

The first large-scale road-building project envisioned by the government in Louisbourg was a road that connected Louisbourg with the area known today as Grand Mira South (see image 2.1)4. This road would begin at the harbour and cut through twenty or so kilometres of thick, dense sapinage, ending at the Mira River opposite the mouth of Salmon River. Historian Margaret Fortier says the following about the road that would later be dubbed “Le grand chemin de Miré” or something along the lines of “The Great Mira Road” in English: “The Minister of the Marine greeted the news of the project with enthusiasm, declaring that completion of such a road would bring settlers to the region and make life in Louisbourg more comfortable. When this road was finished, he continued, other useful roads might be built.”5 Although this project began in 1723, difficulties were encountered during its construction, and it would take some twelve years to complete. That being said, when British engineer John Montresor walked this road in the month of March 1759, he described parts of it as “a pretty good road” – high praise coming from someone who had already travelled through the untamed interior of the North American continent6. Indeed, Montresor says that the French had laid “saplings or sparrs across [parts of the road], so tied down with a small ditch at each side to drain off the water”7. Farms, sawmills and houses sprang up around the shores of the Mira River where the road came to its end. In the early 1750s, the government in Louisbourg settled soldiers and German immigrants in the area, resulting in the creation of two villages – Village de Rouillé and Village des Allemands8 (for more information about The Great Mira Road and the villages of Rouillé and Allemands, listen to our podcast on the subject). In the century following the fall of Louisbourg to the British in 1758, the road came to be known as the Old French Road, and today parts of the original French road have been incorporated into the Gabarus Highway9. Although much of this road still exists as a backwoods trail, parts of the Old French Road are now either inundated or have completely disappeared. Attempting to access it is very dangerous and is highly discouraged.

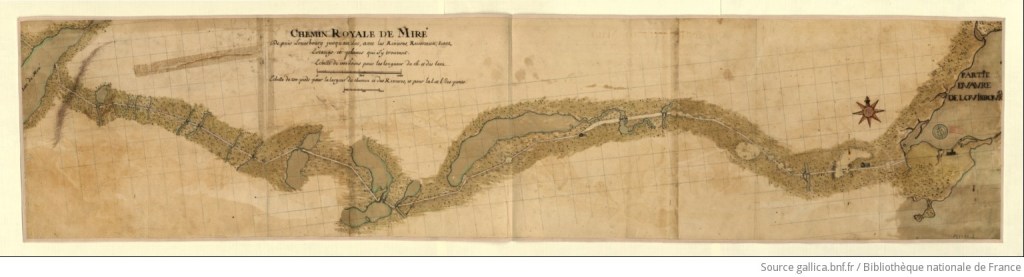

Image 3.1 – The “Chemin de Louisbourg à la Baleine”, part of a map presumably created by engineer Pierre-Jérôme Boucher, 1738. Courtesy BnF Gallica

The Road From Louisbourg to La Baleine

At the same time that the “grand chemin de Miré” was being built, work was being carried out to the northeast of Louisbourg on the “chemin de Louisbourg à La Baleine” (see image 3.1). It would have likely resembled the “grand chemin” in width and construction10. It connected the town of Louisbourg with the rest of the harbour, and then connected the harbour with the settlements east of the capital, like the Laurembecs and La Baleine. Fortier says that “this road promised to be very beneficial to the residents of Baleine who often had to travel to Louisbourg for needed goods and supplies. Although every attempt had been made to keep costs down the minister was told, difficulties repeatedly arose which increased expenses. For the most part these problems were due to the nature of the terrain through which the road passed. In some places there was only “mollières” or “pays trembents”, while in others, “rivières bourbouses” and outcroppings of rock blocked the path”11. By the 1750s, locals had actually started using smaller footpaths that made use of higher ground in order to avoid using the road altogether. Despite its condition, this road has remained in almost constant use from the time it was built to today, and much of the original French road has been incorporated into the Louisbourg Main À Dieu Road which meets Highway 22 just north of the modern town of Louisbourg12.

The Road to the Brothers of Charity Farm

A third major road built in the 18th century was the Brothers of Charity road that ran north from Louisbourg harbour to the Brothers of Charity farm located at Mira Gut. According to a 1738 map created by engineer Pierre-Jérôme Boucher (see image 4.1), the road split into three separate routes some miles north of Louisbourg harbour. One route was a trail that continued north to today’s Albert Bridge on the Mira River, another was a road that continued to the farm, and one veered off towards today’s Catalone Gut. Although the road to Catalone Gut disappeared by 1758, the trail to the Mira seems to run along the same alignment as today’s Devil’s Hill Road and New Boston Road, and the road to the farm along part of today’s Terra Nova Road. The trail to the Mira not only appears in Boucher’s 1738 map, but also Samuel Holland’s map of the southeast coast of Cape Breton published in 1779 and John L. Johnston’s 1831 map of Cape Breton Island. Therefore, it’s likely that this unnamed trail took on greater importance in 1785 when Sydney was founded, it being the most direct route to Louisbourg available at the time. In the 19th century, this stretch of road was no doubt incorporated into the Old Sydney Road and then in into both Devil’s Hill Road and New Boston Road during the late 19th or early 20th century.

Image 4.1 – “Carte des Environs de Louisbourg, avec la Rivière, Partie du Grand Lac et le Chemin de Myré”, part of a map presumably created by engineer Pierre-Jérôme Boucher, 1738. The trail to the Mira, the road to the Brothers of Charity farm and the road to Catalone Gut are clearly indicated. Courtesy BnF Gallica.

Governor de Raymond’s Vision

In the last decade of French rule in Cape Breton, three other roads were ordered by the governor, the Count de Raymond. They were the “Chemin Raymond”, which connected the Mira River to the Bras d’Or Lakes, and the “Chemin Rouillé” which also connected Port Dauphin (St Anns) to the Bras d’Or. The third was the portage road mentioned previously in St. Peters. However, due to their hasty construction, none of them stayed in good condition for very long.

Conclusion

As we’ve seen, the landscape of Cape Breton continues to tell the story of those who once called the island “home” so very long ago. Although the French and their colonial ambitions have long since disappeared from the island, those “silent companions” – the roads and pathways of days gone by – testify to the impact they had on the island some 300 years later.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. [Portefeuille 131 du fonds du Service hydrographique de la Marine consacré à l’Ile du Cap-Breton et à l’Ile de Sable]. 02, [Division du fonds du Service hydrographique de la Marine consacrée à l’Ile Royale – cartes générales] – https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b5901070m/f15.item.r=cap%20breton#

2. MacLellan, J.S. (1918). Louisbourg From its Foundation to its Fall, p. 1

3. MacLellan, J.S. (1918). Louisbourg From its Foundation to its Fall, p. 59

4. MacLellan, J.S. (1918). Louisbourg From its Foundation to its Fall, p. 89

5. The Cultural Landscape of 18th Century Louisbourg –Part Two: The Outports – Roads. Margaret Fortier. 1983

6. Scull, G. D. (Gideon Delaplaine) (1882). The Montresor Journals. p. 189

7. Scull, G. D. (Gideon Delaplaine) (1882). The Montresor Journals. p. 189

8. Du Boscq de Beaumont, G. (1899). Les derniers jours de l’Acadie, 1748-1758, p. 64. Paris : E. Lechevalier

9. The Cultural Landscape of 18th Century Louisbourg – Part Two: The Outports – Roads. Margaret Fortier. 1983

10. The Cultural Landscape of 18th Century Louisbourg – Part Two: The Outports – Roads. Margaret Fortier. 1983

11. The Cultural Landscape of 18th Century Louisbourg – Part Two: The Outports – Roads. Margaret Fortier. 1983

12. The Cultural Landscape of 18th Century Louisbourg – Part Two: The Outports – Roads. Margaret Fortier. 1983

Wow, that is great work! Future podcast ?

Sent from Yahoo Mail for iPhone

LikeLike

gratifying! 99 2025 Falling Through the Cracks: An 18th Century Acadian Village on the Bras d’Or Lakes? radiant

LikeLike

Pingback: Remarkable Stories From the Lost Settlements of 18th Century Cape Breton | The Lost World of Cape Breton Island