LAST UPDATED NOVEMBER 22, 2025

This post builds on the research found in the article “The Lost Settlements of 18th Century Cape Breton Island – St. Esprit, Allemands, Rouillé and Espagnole.”

Writing about events that took place during his tenure in Louisbourg, the Chevalier de Johnstone identified the very moment he realized that the Maritime region was headed for another full-scale war. That watershed moment was the peace-time seizure of a French merchant vessel by a British warship off of Nova Scotia1 in the year 1750. As it turned out, things would eventually culminate into the conflict that Johnstone had long foreseen – the French and Indian War. Hostilities would begin in 1754 between the North American colonies of Great Britain and France, but would soon grow to include the European powers as fighting spread across the globe. This new conflict ensured that the next few years would be some of the most tumultuous that the Maritimes would ever see, especially for the island of Cape Breton. By the end of the war in 1763, the cultural landscape of Cape Breton would be forever changed – thousands of people would be removed from the island and shipped back to France, and the once busy port of Louisbourg would be reduced to a position of redundancy when Cape Breton was eventually grafted onto the Province of Nova Scotia. The settlements of St. Esprit, Allemands, Rouillé and Espagnole, four communities established in Cape Breton during the time of the French, would be particularly affected by the instability and upheaval of that decade. Not only would it cement their fall into obscurity, it would also spell the end of their very existence.

Several documents are instrumental to our understanding of what life was like in these four lost communities. One of those documents is “Les Derniers Jours de l’Acadie, 1748-1758,” which is a collection of correspondence that ran through the hands of Le Courtois de Surlaville, an officer who also served in the Louisbourg garrison during the early 1750s. Another is Sieur de La Rocque’s census of Île Royale, compiled during the brutal winter months of 1752. Other primary sources include the journals of the very people who were eye-witnesses to these long lost communities, like the canadien Charles Deschamps de Boishébert and British engineer John Montresor. In fact, in at least one instance the journal entries are known to have been made on site. These kinds of invaluable primary sources are now preserved in places like the Bibliotheque et Archives Nationale de Québec and Library and Archives Canada.

The following events are pulled from this kind of documentation. Some are stories of heroism. Others portray the cruel effects of war, and still others tell the tale of seemingly endless displacement. These events could be seen as critical moments in these communities’ brief existence.

St. Esprit

NOTE: For more information on St. Esprit, listen to “Episode 5 – The Lost Harbour of St. Esprit” on The Lost World of Cape Breton Island Podcast.

In our last article about the lost settlements of 18th century Cape Breton, we introduced St. Esprit, where we said the following about this obscure cod-fishing hub: “St. Esprit was one of the outports that developed after the French evacuated Placentia, Newfoundland in the year 1713. The community grew so quickly that, after only a few years, it became necessary for the colonial administration to appoint not only a harbour-master but also an intendant. The book Control and Order in French Colonial Louisbourg says about St. Esprit: “In 1734 there were 234 residents; three years later there were 546”.” This was a very large settlement in Cape Breton at the time. Established about thirty kilometres up the coast from Port Toulouse (today’s St. Peter’s), it was an easy target for the New Englanders during the first siege of Louisbourg in 1745, and the outport was subsequently attacked. After the war, the community never did regain its former significance. The habitants of St. Esprit during the 1750s were people native to places like Acadia, Niganiche (present-day Ingonish) and Port Toulouse, but also places like St. Malo and the region of Rochefort in France2. The population, however, would plateau at about 100 people3. Interestingly, if the French ever did make a map of St. Esprit during the 18th century, it has either been destroyed, mislabelled or has never been published, hence why the exact location of the settlement is unknown today.

Three centuries of North Atlantic storms have forever altered the coastline of this once bustling harbour, but the sandbanks that line the coast have no doubt remained a constant feature of the community since the time of Louisbourg. One could imagine standing on those sandbanks on a clear night three hundred years ago and seeing the flickering lights of shipping on the horizon. During the 1750s, the waters off Cape Breton were rife with danger, as the beginning of the French and Indian War ushered in an era of further unrest and turmoil for the entire Maritime region. Instead of seeing the flickering lights of far off shipping, one could likely see the flickering lights of British warships spreading across the North Atlantic like a net in an attempt to catch French vessels bound for Cape Breton.

The year 1757 saw the height of these mounting maritime tensions. Sir Francis Holburne’s fleet from Halifax spent the summer blockading the port of Louisbourg in preparation for a full scale assault that in the end was postponed to the following year. Sitting safe and sound inside the port was a French fleet of equal size and under direct orders to not engage the British fleet that had spent the last few months taunting them. This standoff continued until the end of September, when mariners began to observe something peculiar on the horizon.

One mariner recorded exactly what it was he was seeing: “Out at sea we noticed a mist which spread towards the harbour in the night. On Friday there was a slight S.E. wind with a little fog. Saturday it veered from S.E. to E.S.E nice and fresh…at 11 o’clock at night the wind got very violent, but two hours after midnight it was even stronger, till 11 o’clock this morning, when it veered to the south and soon to the S.W. I have never seen anything like it.”4

A powerful hurricane was making landfall. Another sailor in Louisbourg harbour described the destruction that followed: “More than 80 boats and skiffs of the squadron were tossed by the waves and smashed, most of them on the shore, a number of men on board them perishing. More than 50 schooners and boats met the same fate…Sailors, who have been 50 years afloat, say that they never saw the sea so awful. The ramparts of the town were thrown down, and the water inundated half of the town, a thing which has never been seen. The sea dashed with such tremendous force on the coast that it reached lakes two leagues inland…”5

Holburne’s fleet clawed their way offshore in a desperate attempt to get out to open sea. All but one of Holburne’s ships managed to escape – HMS Tilbury, which floundered on the coast of none other than St. Esprit.

Once word had reached Louisbourg that a British ship had been wrecked in the vicinity of St. Esprit, a rescue party was dispatched to give aid to the survivors. The going, however, was difficult. First of all, their ship was turned back by contrary winds, so they had to go on foot instead. There was no road to St. Esprit from either Louisbourg or St. Peter’s, so the rescue party had to push their way through 50 kilometres of thick, coastal forests. “Our troops had great difficulty in reaching the scene of the wreck, owing to the floods in many localities which the gale had caused the sea to submerge,”6 said someone in the rescue party. Another reason the rescue party was dispatched so promptly was because the French believed that if the Mi’kmaq arrived at the site before them that they would kill the surviving crew members as soon as they made it to shore. Their fears about the Mi’kmaq, however, would prove to be completely wrong.

Figure 2.1 – HMS Foudroyant, launched in 1798, ran aground off Blackpool, England in 1897. Although slightly larger than the Tilbury, this image provides some perspective on just how large these ships were and also the skill required by the Mi’kmaq rescuers, who climbed aboard the wreck and assisted the survivors off the ship.

Upon the party’s arrival to St. Esprit, they found 230 of the 400-strong crew alive, aided by the very people the French feared would kill them. According to one report, a Mi’kmaq chief “came forward and reassured them [the crew of the Tilbury], saying “fear not, since the hurricane has brought you to shore we are coming to your relief, but if you had come to make war upon us, not one of you would be safe.” The Indians themselves went on board the ship to help others get off.”7

The ship was never salvaged, but thanks to the Mi’kmaq, the majority of the sailors aboard the Tilbury survived. The shore that she ran aground on still bears her name, Tilbury Rocks (see figure 2.2), and for many years cannons and coins would often wash up on shore.8

Though not identifying the man by name, it’s possible the Mi’kmaw chief who aided in rescuing the crew of the Tilbury was Jeannot Pequidalouet. Jeannot was the chief in Cape Breton during the time of Louisbourg and shows up frequently in 18th century records and correspondence, and it’s likely that he was in the vicinity of Louisbourg during the period of heightened military activity in the summer of 1757.

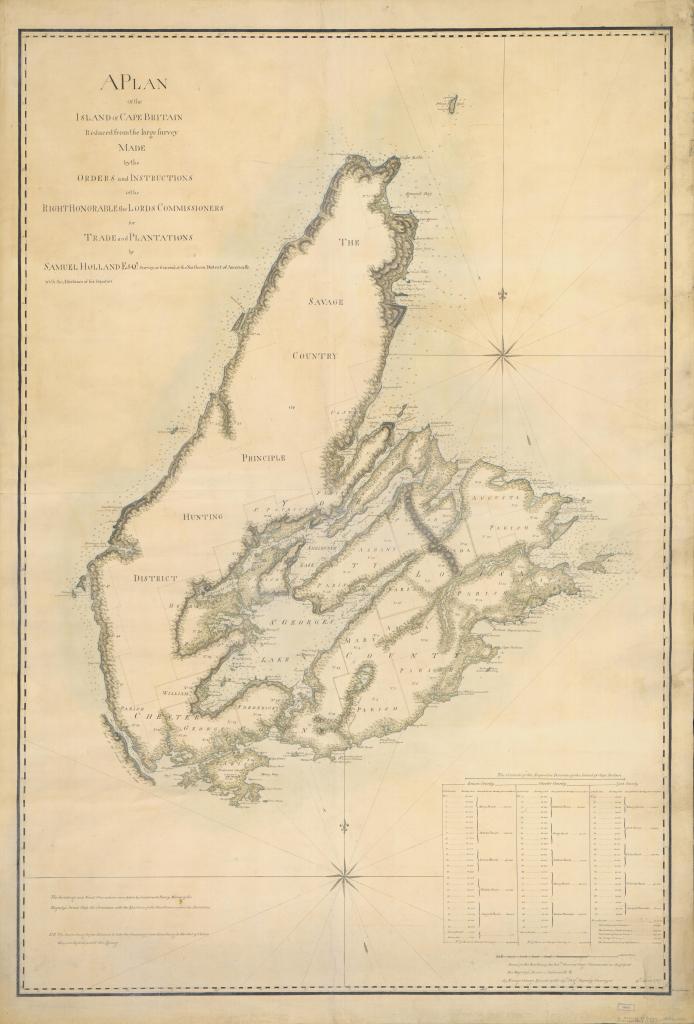

About ten years after these events, British surveyor Samuel Holland visited the area of St. Esprit. Holland’s letters regarding Cape Breton as well as his final observations delivered to the British Board of Trade in 1768 can now be found in the publication “Holland’s Description of Cape Breton Island and Other Documents,” compiled by archivist D.C. Harvey. Holland was assessing Cape Breton Island for future potential settlement, and retraced the steps of many of the engineers and surveyors who had criss-crossed Cape Breton before him. He found that St. Esprit, like many communities since the second siege of Louisbourg in 1758, had been abandoned. Holland reported that many houses had simply been left to rot, which gives the impression that the community did not suffer the same fate as it had during the first siege in 1745 – namely, being seriously targeted and attacked by the British and New Englanders.9 What happened to the inhabitants, however, is unclear. Some were likely deported, and others probably fled to the woods with the Mi’kmaq. Though never to the extent that it had seen during what Holland called “the French time,” St Esprit would again see settlement around the year 1840 when Scottish families began to settle in the area after the Highland Clearances. Today, the area of St. Esprit retains the name given to it by the French some three hundred years ago.

Figure 2.2 – Tilbury Rocks in St. Esprit. In the foreground is a cannon from the wreck of HMS Tilbury. Courtesy Archives Nova Scotia.

Allemands & Rouillé

NOTE: For more information on Allemands and Rouillé, listen to “Episode 6 – Allemands and Rouillé: The Mira River’s Lost Settlements” on The Lost World of Cape Breton Island Podcast.

The 1750s brought much uncertainty to the villages of Allemands and Rouillé. In fact, from their very inception in the year 1752, the villages were exposed to a number of challenging conditions – poor choice of location meant that the settlements were too far away from the capital, the soil was acidic, and particularly for Rouillé, its inhabitants were considered to be lazy10. A man named Le Roy had built a sawmill in the area, but ran out of good quality wood by 175611. In the centre of Allemands was a marsh which helped in the growing of wheat, but in the end it did little to help the overall situation12. Five years after their initial settlement, both communities were – not surprisingly – struggling. A census taken in 1753 recorded a total of 78 people living in these two villages13, but four years later, the population was much reduced. The Cob, Meyoffer, Rouf, Keiler, Jacob and Andrea families were some of the inhabitants recorded as still living in Allemands around 175614. In Rouillé, the St. Brieux, Paveur, André, Framboise and Savory families, predominantly French, were among those still making a go of it in 1757.15

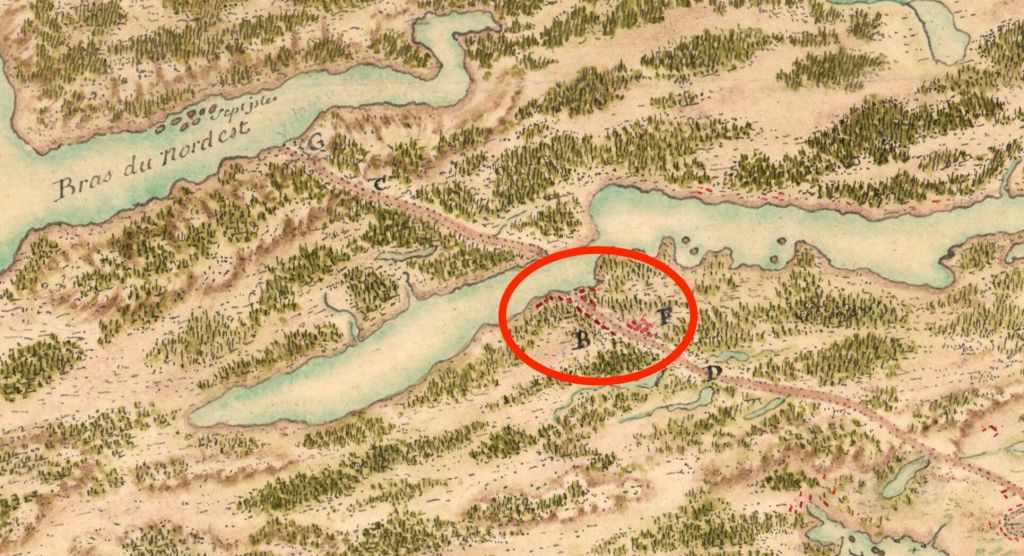

Figure 3.1 – “Plan de l’Isle Royalle, 1752.” The body of water in the centre of the image is the Mira River in the area of present-day Grand Mira North, Grand Mira South, Campbelldale and Huntington. Circled in red are the villages of Rouillé and Allemands. The Great Mira Road is represented by the letter D, and Raymond’s Road is represented by the letter C. click here to view the entire map. Courtesy BnF Gallica

Both villages had been deliberately settled on the most important artery in Cape Breton at the time – the Great Mira Road, or le grand chemin de Miré. The Great Mira Road had been cut through thirty-or-so kilometres of rough coastal forest during the 1730s, connecting the shores of Louisbourg harbour to the Mira River in the vicinity of today’s Grand Mira South. It allowed movement to and from the interior of the island for hunters, land owners, millers and also for couriers bringing official correspondence between Canada and Île Royale16. Today, much of the Great Mira Road still exists as a backwoods trail known locally as ‘The Old French Road.’ Unlike St. Esprit, detailed maps of Allemands and Rouillé have survived to our day, however the section of the Great Mira Road on which these villages were built disappeared sometime during the first half of the 19th century17, and so the precise location of these settlements are still unknown.

To add to those challenging conditions just mentioned, the Mira River region was particularly susceptible to the tides of war that would often submerge the island during the first half of the 18th century. The area had seen much looting and destruction during the first siege of Louisbourg in 1745 when New England scouting parties meandered through the area, burning homesteads and making off with whatever they could find18. The Great Mira Road could be easily reached from Gabarus Bay by a “chemin plaqué,” or a kind of marked trail, that ran through the woods and intersected the road around Twelve Mile Lake19, making access to the Mira (and any houses along the way) that much easier (figure 3.2).

To make matters even worse, it became apparent that the British, who were unable to carry out their expedition against Cape Breton in 1757 would lick their wounds in Halifax until the ice cleared enough for them to make another attempt. In the coming year, war finally did come to these villages’ doorsteps. The events that followed would culminate not only in the capture of Cape Breton, but the destruction of these two communities.

On June 8 1758, the British succeeded in landing at Anse de la Cormorandière (Kennington Cove), and as they landed more troops in the days that followed, scouting parties began to spread through the area. A French officer named Charles Deschamps de Boishébert arrived at the Mira River along with 300 men not long after the British landing. Boishébert had been tasked with keeping the field beyond the walls of the fortress in case of a siege, and arrived in Cape Breton after a tedious voyage all the way from Québec. Making the trek from Port Toulouse (St. Peter’s) to the Mira via the Bras d’Or Lakes, Boishébert and his party finally arrived at the Mira on July 1. They had sailed up the southernmost coast of the Bras d’Or and left their boats on the shore, proceeding on foot down Raymond’s Road, or le chemin Raymond.

Raymond’s Road was a communication route that had been hastily cut through the untouched interior of the island about eight years prior to these events. It was named after Louisbourg’s most eccentric governor, the Count de Raymond, who ordered its construction so that Port Toulouse and Port Dauphin (St. Ann’s) could keep in closer contact with the capital, Louisbourg. The road meandered north from the Mira River, then westward around the bend of Salmon River before veering northwest, blazing a trail straight up and over the Bras d’Or Hills and down to the shores of the Bras d’Or in the vicinity of today’s Big Pond or Ben Eoin. Despite the fact that the road hadn’t been cleared with as much precision as the Great Mira Road had been, Raymond’s Road appears on maps of Cape Breton as late as 182920.

As a side note, Boishébert was joined by Acadian men from the Port Toulouse militia. Historian Ann-Marie Lane Jonah says that Pierre Bois, the first settler to the region of Chéticamp thirty years later, “was part of the Acadian militia in Île Royale that joined forces with the company led by Charles Deschamps de Boishébert.”21 It’s possible that Bois was an eye-witness to the following events. His wife was none other than Jeanne Dugas, designated a “Person of National Historic Significance” in Canada in 2013.

As soon as Boishébert arrived on the Mira, skirmishes between his men and the British camps broke out up and down the length of the Great Mira Road, and the villages of Allemands and Rouillé were literally caught in the middle. This brings up the question, where did the families still living in the villages go for shelter during this time? I haven’t found documentation that sheds light on the answer. Perhaps they fled to Louisbourg before the British landing, or maybe they joined Boishébert’s camp on the Mira. Regardless, Boishébert was soon forced to retreat as the British “advanced up the Rouillé road and that of the Mira, encamping detachments of 800 men.”22 Boishébert fled back up Raymond’s Road and across Cape Breton to the mainland, bringing many Acadians from St. Peter’s with him to back to Miramichi at the surrender of Louisbourg.

About nine months later, British engineer John Montresor (figure 3.5), along with 40 soldiers marched along the Great Mira Road on their way to the Bras d’Or Lakes. Writing in his journal from the shores of the Mira on March 28th 1759, he elaborates on what happened to these two villages after the events of the summer past: “Marched thro’ the remains of a village called Village d’almagne, burnt down, this spot was generally called by the French, Les Deserts the land being open, free from trees…after crossing the bridge commences another village called by the French village de Rouler (burnt)…situated on the ascent of Montaigne Diable, or Devil’s Mountain whose descent leads to the Lake [the Mira River] and on which continues the remainder of the village de rouler.”23 There is no indication in Boishébert’s journal that Boishébert himself gave the order to burn down the villages during their retreat, so it is likely that it was the British who did so as they advanced up the Great Mira Road in the wake of Boishébert’s retreat.24 In total, the villages existed for only 6 years.

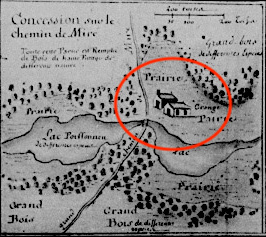

Though likely not considered part of either Allemands or Rouillé, three properties also situated along the Great Mira Road are mentioned between the journals of Boishébert and Montresor. One of Boishébert’s officers burns down a home that was being used as a British guardhouse, but we’re given no further information about its whereabouts except that it was located “by the woods.” Montresor mentions a certain “Portic’s Farm,”25 which was situated somewhere off the Great Mira Road around Twelve Mile Lake. Nothing more is known about either “Portic,” his farm, or if this farm survived the events of 1758. More prominently described by Montresor is the homestead of Joseph Lartigue (“Jean Lertie” according to Montresor), located in the area of today’s Oceanview and French Road. Joseph Lartigue was a member of the colony’s Conseil Supérieur and also served as a judge in Louisbourg who, at the time of his passing in 1743, owned multiple properties around the island. This particular property was where Montresor and his 40 soldiers slept on the evening of March 27th 1759. According to Montresor, this concession had a house and a barn not far away. This is confirmed by a map created sometime after Lartigue’s death depicting all the property still owned by his widow (see figure 3.4). Throughout his journal, Montresor takes the time to make brief but descriptive notes on what it was he was seeing, and usually mentioned when a house they came upon had been burnt down, but in this particular entry he mentions Lartigue’s house only in passing. It’s possible that the house had been spared destruction during the siege of Louisbourg and was still standing at that time Montresor and his men spent the night. No mention is made by Montresor of who, if anyone, was living in the house at the time. In fact, Montresor does not seem to encounter anybody except the soldiers of his own party during the entire journey from Louisbourg to the Bras d’Or Lakes.

These passing remarks scribbled into Montresor’s journal back in 1759 provides us with only a fleeting glimpse of reality for the people who lived on the Great Mira Road during this era. And almost by accident, Boishébert, while writing a journal he likely thought would be seen only by the military, revealed the final moments of Allemands and Rouillé as living, breathing, communities. It’s difficult to comprehend the isolation that many of these homesteads would have been exposed to. One could very accurately describe these settlers as living on a kind of “frontier.” According to Le Courtois de Surlaville, it would take more than five hours to get to Louisbourg from Rouillé and Allemands, making a trip to town in less than two days impossible26. Of course, there were larger homesteads located even farther from Louisbourg than those situated along the Great Mira Road. J.S. McLennan, writing about these kinds of larger far-flung estates, makes the following observation: “The description of these farms would indicate that this outflow of enterprise and population would come from a more thriving town [referring to Louisbourg] than the official letters described. Scarcity of food is a serious thing, but satisfaction, with her offspring comfort and energy, treads close on the heels of supply.”27

About ten years later, the area of the Mira in which Allemands and Rouillé used to exist was also visited by Samuel Holland. Holland says that he was actually able to speak to a German man “who was a settler at the first establishment of German Village [Allemands].”28 Although not specifying where he spoke to him, it’s likely that he met this German man during his survey of Cape Breton. Therefore, it’s probable that some Germans managed to remain on the island after the events of 1758.

After a seventy year hiatus, the area would again begin to see settlement when Gaelic speaking families arrived in Cape Breton from Scotland would set down lasting roots. This area became known succinctly as “French Road,” the name we are familiar with today.

Espagnole

Much like the villages of Allemands and Rouillé down on the Mira, Baie des Espagnols (commonly referred to as “l’Espagnole” by the people of Île Royale29), was settled only after Cape Breton Island was returned to the French in 1749. While other large settlements like Niganiche (Ingonish) ceased to exist30 after the fall of Cape Breton to the New Englanders and British in 1745, settlements like Espagnole were brought into existence upon its return to the French at the end of the war. Prior to that time, Baie des Espagnols was sparsely populated, and as of 1734, it had no permanent inhabitants whatsoever31. By 1752, its population had exploded to 190 people, one of the highest concentrations of people anywhere on the island32. It’s unclear if Espagnole was a concentration of homes in a particular area or if the homes were distributed evenly along the shores of the entire harbour. Some thirty years later, Baie des Espagnols would be the site of a new capital for the British colony of Cape Breton Island. It would be dubbed Sydney, but its former name, ‘Spanish Bay,’ would be forever connected with the harbour.

The Acadians who first settled Baie des Espagnols were from the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia. These families immigrated to Cape Breton when the British founded a new settlement in Chebucto, now known as Halifax, in 1749. Perhaps the choice of Baie des Espagnols had to do with the fact that it had a better climate than that of Louisbourg or Port Toulouse, hence lending itself to farming. It was also situated closer to the Gulf of St Lawrence, and therefore farther off the beaten path than other coastal communities that had been targeted during the last war. Robert Shears in the paper “Examination of a Contested Landscape: Archaeological Prospection on the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia” says about these Acadian who chose to leave their ancestral home: “Fearful of their future in British-controlled territory, Acadians sought the security of land that was both French and Catholic. Though Île Saint-Jean became the preferred destination for migrant Acadians, Île Royale saw a significant influx of refugees as well.”33 Not long after the Acadian families arrived, the governor of Île Royale, Count de Raymond, sent soldiers to also settle the area in order to marry the daughters of Acadian families, all in an effort to make the island self sufficient.34

Sieur de La Rocque, while undertaking the monumental task of an island-wide census in 1752, stayed in Espagnole and preserved a ‘photograph in time’ of this new Acadian/soldier settlement. Despite his usual matter-of-fact precision, La Rocque felt it was worth noting that one of the habitants, a certain Jean Boutin, was “alone in a small house that his children helped him to build. He makes hand-barrows and other small things for his own amusement.” Boutin was 76 years old at the time of the census. It’s often a challenge to humanize personal data that’s already centuries old, but La Rocque’s brief remark about what this man did in his spare time is a stark reminder that on the other side of each of these notations was a living, breathing person. Jean Boutin was joined in Espagnole by four of his sons – Antoine, Paul, Charles and Joseph.35

The settlement of Espagnole proved to be a challenge for the colonial administration in Louisbourg. Robert Shears continues: “Only a year passed before the settlement at Baye de Espagnols was described as unlikely to succeed. Even though the Acadians had been tasked with, in the span of a year, preparing virgin woodland for habitation and cultivation and producing a sustainable harvest, they were characterized by French financial commissary Jacques Prévost as “indolent” and “lazy,” and in need of continued government assistance. They were regularly accused of being unwilling to clear land and follow direction from the French Crown. In 1754, the return on the crop sown was not large enough to provide for the inhabitants, causing the Acadians to present to the new Governor of Île Royale, Augustin de Boschenry de Drucour, a “request to leave their habitations”, which they claimed “could never produce enough to feed and keep alive a family.”36

Jean Boutin, the man who would make “hand-barrows and other small things,” likely passed away sometime around 1754. His sons Paul and Charles were among the Acadians who left Espagnole for Lunenburg, where they appear on a victualling list in 1755. Little did they know that they had emigrated back into a powder keg that was about to explode. Later that same year, the British government of Nova Scotia began the systematic removal of Acadians from the province, and despite taking the oath of allegiance, Paul, Charles and their families were rounded up during the Deportation of the Acadians and imprisoned on Georges Island in Halifax harbour. Stephen White, an Acadian genealogist says that Paul, Charles and their families “were among approximately 50 Acadians deported from Halifax to North Carolina aboard the sloop Providence, in 1755.”37

The Boutins would spend some twelve years in the American colonies, jumping from place to place in an attempt to eke out an existence in the aftermath of their deportation. At some point during this time, Charles passed away38. Finally, around 1767 when the Boutin family were in Maryland, news reached them that the Spanish government in Louisiana was welcoming Acadians to the colony, and according to Steven A. Cormier, “they [the Acadians in Maryland] pooled their meager resources to charter ships that would take them to New Orleans.”39 In the end, it was only Paul Boutin and his immediate family that boarded the ship and settled in Louisiana at San Gabriel on the Mississippi.40

The rest of the Boutin family that stayed in Baie des Espagnols fared no better than Paul and Charles. At the fall of Cape Breton to the British in 1758, the Boutin’s who stayed on the island were also rounded up and shipped back to St. Malo41, never to be reunited as a family again. Such was the incredibly challenging reality of life in Cape Breton Island and the maritime region as a whole during the 1750s.

Conclusion

Unlike some Cape Breton communities that quietly faded out of existence with the passing of time, the communities of St. Esprit, Allemands, Rouillé and Espagnole came to an abrupt end, and so too the processes of folklore and local history that would have naturally developed around them. Sadly, these brief stories are no longer tales that can be passed on from generation to generation or from person to person. With the strife that the 1750s brought to the region, there was simply nowhere for the stories to go except with the people when they left the island for the last time. They are now tales that can only be told by piecing together the journals, censuses, and official papers that have survived three hundred years of decay. In the span of only a few decades, what’s physically left over begins to disappear. Old houses are reabsorbed into the earth. The old roads, discarded as usable routes as the migration patterns of people change over the years, take on a sort of mythical element associated with bygone days. Since the majority of these events are now solely preserved within the yellowed pages of near ancient historical documentation, it begs the question – how many more of these kinds of stories are yet to be discovered?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Johnstone, James. The campaign of Louisbourg, 1750-’58, p.4

- Sieur de La Roque. “Recensement de l’Île Royal et de l’Île Saint-Jean”, p. 21 -30 – https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c4582/24

- Sieur de La Roque. “Recensement de l’Île Royal et de l’Île Saint-Jean”, p. 21 -30– https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c4582/24

- MacLellan, J.S. (1918). Louisbourg From its Foundation to its Fall, p. 207

- MacLellan, J.S. (1918). Louisbourg From its Foundation to its Fall, p. 208

- MacLellan, J.S. (1918). Louisbourg From its Foundation to its Fall, p. 209

- MacLellan, J.S. (1918). Louisbourg From its Foundation to its Fall, p. 209

- MacLellan, J.S. (1918). Louisbourg From its Foundation to its Fall, p. 210

- Holland, Samuel (1935). Holland’s Description of Cape Breton Island and Other Documents, p.81.

- Fortier, Margaret (1983). The Cultural Landscape of 18th Century Louisbourg – Miré Region – Rouillé and German Village

- Fortier, Margaret (1983). The Cultural Landscape of 18th Century Louisbourg – Miré Region – Rouillé and German Village

- Fortier, Margaret (1983). The Cultural Landscape of 18th Century Louisbourg – Miré Region – Rouillé and German Village

- MacLellan, J.S. (1918). “Louisbourg From its Foundation to its Fall,” First Edition, Appendix III

- Fortier, Margaret (1983). The Cultural Landscape of 18th Century Louisbourg – Miré Region – Rouillé and German Village

- Fortier, Margaret (1983). The Cultural Landscape of 18th Century Louisbourg – Miré Region – Rouillé and German Village

- Sauriol, M (2004). Voyage en hyver et sur les glaces de Chédiäque à Québec. Cap-aux-Diamants, (78), 43-43

- Crown Land Map Index #132 – Department of Lands and Forests – Nova Scotia. https://novascotia.ca/natr/land/indexmaps/132.pdf

- MacLellan, J.S. (1918). “Louisbourg From its Foundation to its Fall,” p. 89

- Boucher, Pierre-Jérôme (Auteur présumé du texte), “Carte des Environs de Louisbourg.” Bibliothèque Nationale de France – https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b5901078x/f15.item.r=chemin%20de%20mire

- Haliburton, Thomas Chandler. “A New Map of Nova Scotia compiled from the latest surveys expressly for the Historical and statistical account of Nova Scotia, 1829.”

- Lane-Jonah, A. M. (2016). Everywoman’s Biography: The Stories of Marie Marguerite Rose and Jeanne Dugas at Louisbourg. Acadiensis, 45(1), p. 54. Retrieved from https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/Acadiensis/article/view/24584

- Boishébert, Charles Deschamps. Journal de ma campagne de Louisbourg. Bulletin des Recherches Historiques, vol. XXVII, No. 2 (1921), p.50

- Scull, G. D. (Gideon Delaplaine) (1882). The Montresor Journals. p. 189, 190

- Boishébert, Charles Deschamps. Journal de ma campagne de Louisbourg. Bulletin des Recherches Historiques, vol. XXVII, No. 2 (1921), p.50, 51

- Scull, G. D. (Gideon Delaplaine) (1882). The Montresor Journals. p. 189

- Du Boscq de Beaumont, G. (1899). Les derniers jours de l’Acadie, 1748-1758, p. 65. Paris : E. Lechevalier

- MacLellan, J.S. (1918). “Louisbourg From its Foundation to its Fall,” p. 89

- Holland, Samuel (1935). Holland’s Description of Cape Breton Island and Other Documents, p.78.

- Du Boscq de Beaumont, G. (1899). Les derniers jours de l’Acadie, 1748-1758, p. 112, 308. Paris : E. Lechevalier

- Pouyez, Christian. La population de l’ile Royale en 1752, p. 7.

- Pouyez, Christian. La population de l’ile Royale en 1752, p. 11.

- Pouyez, Christian. La population de l’ile Royale en 1752, p. 11.

- Shears, Robert (2013).“Examination of a Contested Landscape: Archaeological Prospection on the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia,” p.30

- Du Boscq de Beaumont, G. (1899). Les derniers jours de l’Acadie, 1748-1758, p. 103, 104. Paris : E. Lechevalier

- Recensement de l’Ile Royale et de l’Ile St Jean par Sieur de La Rocque, 1752. p.45, 46

- Shears, Robert (2013).“Examination of a Contested Landscape: Archaeological Prospection on the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia,” p.33

- Cormier, Steven A. The Acadians of Louisiana: A Synthesis – Book 10, “Boutin.” http://www.acadiansingray.com/Acadians%20of%20LA-Intro-5a.htm#BOOK_SEVENns

- Cormier, Steven A. The Acadians of Louisiana: A Synthesis – Book 10, “Boutin.” http://www.acadiansingray.com/Acadians%20of%20LA-Intro-5a.htm#BOOK_SEVENns

- Cormier, Steven A. The Acadians of Louisiana: A Synthesis – Book 10, “Boutin.” http://www.acadiansingray.com/Acadians%20of%20LA-Intro-5a.htm#BOOK_SEVENns

- Cormier, Steven A. The Acadians of Louisiana: A Synthesis – Book 10, “Boutin.” http://www.acadiansingray.com/Acadians%20of%20LA-Intro-5a.htm#BOOK_SEVENns

- Cormier, Steven A. The Acadians of Louisiana: A Synthesis – Book 10, “Boutin.” http://www.acadiansingray.com/Acadians%20of%20LA-Intro-5a.htm#BOOK_SEVENns

© J.M Bourgeois 2020-2023