LAST UPDATED NOVEMBER 22, 2025

As a general rule of thumb, once the earth has been formed or shaped by people, it keeps that shape for a very, very long time. An example of this can be seen at Fort Ticonderoga (Carillon), where the trenches dug by French soldiers during the Seven Years War are still clearly discernible today. Another example is Wolfe’s redoubt which sits not far from the Visitor Centre at the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site, a pile of earth formed into the shape of a hollow square that’s remained in that shape for the last 250 years. So finding evidence of human interaction with the ground through farming or construction is fairly easy to spot if you know what to look for.

France’s imprint on the landscape of Cape Breton Island outside of the Fortress of Louisbourg was minimal. For one, less than fifty years passed from the founding of the Colony of Île Royale to its fall at the hands of the British, so there simply wasn’t much expansion beyond the main settlements of Louisbourg, Port Toulouse (Saint Peters) and Port Dauphin (St Anns). Another reason for this is since the primary concern of the settlers in Île Royale was the cod-fishery, it was the shoreline that saw the heaviest development, and due to 250 years of erosion the shoreline has greatly receded, erasing any footprint that may have existed.

That being said, there are features of French settlement that have survived down to today. A quick trek off the beaten path will reveal many of them. Here are three features that have survived from the days of Île Royale down to our day.

The Barachois Bridge

During the 18th century, the barachois at the bottom of Louisbourg harbour was the location of what was known as the fauxbourg, a neighbourhood of Louisbourg that existed outside of the fortress walls. The majority of inhabitants in this area were fisherman, and their properties were set up for the purpose of processing and drying cod. The road that ran from the Dauphin Gate, Louisbourg’s busiest entryway, hugged the shore of the harbour, wrapped around the barachois and then continued around the rest of Louisbourg harbour eastward (bottom left). At sometime during the first half of the 18th century, certain maps of Louisbourg began to include a bridge in their depiction of the fauxbourg while others did not. However, if we compare a modern satellite image of Louisbourg (bottom centre) with an 18th century map that depicts the 1758 Siege of Louisbourg, we find that the remains of that bridge or perhaps a causeway are still visible today (bottom right).

The Great Mira Road (Le grand chemin de Miré)

NOTE: For more information about le ‘grand chemin de Miré’, listen to “Episode 6 – The Lost Villages of Allemands and Rouillé” from The Lost World of Cape Breton Island Podcast.

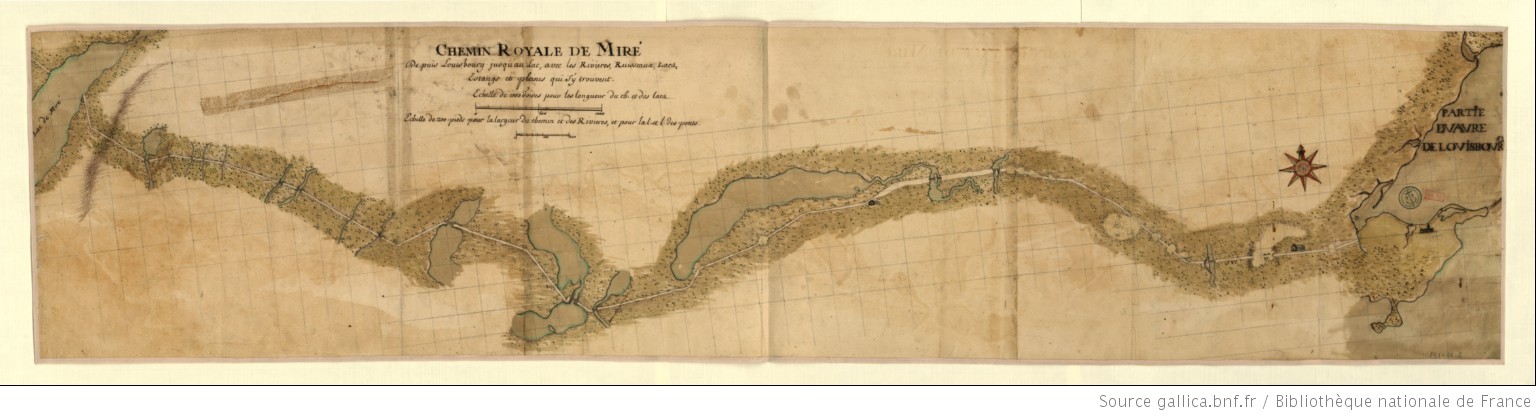

The Great Mira Road, or Le grand chemin de Miré, was one of the largest feats of engineering undertaken by the French outside of the Fortress of Louisbourg. It cut through twenty-or-so kilometres of thick coastal forest from Louisbourg harbour, weaving through present-day Cavanagh’s Lake, Kelly’s Lake, along the bottom shore of Twelve Mile Lake where it turned north, finally ending at what the French called The Ferriage1 on the shores of the Mira River opposite Two Rivers Wildlife Park. With over 25 bridges2 and at least ten feet wide, this road was a critical piece of infrastructure for 18th century Cape Breton. It allowed movement to and from the interior of the island for hunters, land owners, millers and also for couriers bringing official correspondence between Canada and Île Royale3. Many homesteads existed along the road during the time of Louisbourg, including properties owned by Pierre Boisseau, inn-keeper, Louisbourg judge Joseph Lartigue as well as the villages of Rouillé and Village des allemands closer toward the Mira. Marked as the Old French Road on today’s topographic maps, The Great Mira Road has, surprisingly enough, survived almost in its entirety. Its entrance is located at the very end of Park Service Rd., marked only with a small wildlife refuge sign. Once it comes out of the woods beyond Twelve Mile Lake, it connects to Oceanview Rd., then becomes the Gabarus Highway and continues along Campbelldale Rd. for a while where it would’ve veered northward toward French Village Lake. This last stretch of the road is the only part that doesn’t exist today, nor does it correspond to any contemporary road or community.

A word of caution: certain parts of the Great Mira Road between Park Service Rd. and Oceanview Rd. have become either inundated or overgrown, so attempting to walk the trail would be very dangerous. I suggest exploring it with Google Earth instead.

Path to the Mira (Devil’s Hill Falls Trail)

Devil’s Hill Falls Trail off of New Boston Rd is said to be the remains of an old path that ran from present-day Albert Bridge to the larger Brothers of Charity road, which in turn connected their property at Mira Gut to Louisbourg. Although almost impossible to confirm or deny simply because the maps the French made only provide a general idea of a road’s location and route, Devil’s Hill Trail does line up pretty well with what information they did include about this 18th century path.

The roads in the vicinity of Albert Bridge, Mira Gut and Catalone were not built by the government of Île Royale, and as historian Margaret Fortier notes, “All [these roads] could have existed as paths cut by inhabitants to facilitate their reaching their properties or cutting wood.” In 1757, the French engineer Poilly took the Path to the Mira on his tour of Cape Breton Island and found that a bridge had been built over Rivière à Durand (Catalone River) and also that Longevin, whose homestead was found on the north shore of Albert Bridge, kept a boat to ferry people across the Mira. However the path ended at Albert Bridge and did not continue on the north shore of the Mira River4.

Although it’s true that little has survived from the days of Louisbourg, by just going a little off the beaten path we can still see for ourselves the imprint left by the French on Cape Breton Island so many hundreds of years ago.

_____________________________________________________________________

- The Montresor Journals – p. 190

- The Cultural Landscape of 18th Century Louisbourg – Margaret Fortier. 1983

- Sauriol, M (2004). Voyage en hyver et sur les glaces de Chédiäque à Québec. Cap-aux-Diamants, (78), 43-43

- The Cultural Landscape of 18th Century Louisbourg – Margaret Fortier. 1983