Having miraculously survived an apocalyptic 66-day North Atlantic crossing, the Chevalier de Johnstone arrived in Louisbourg on the 13th of September 17501 aboard L’Iphigénie, a merchant ship owned by Louisbourg businessman Michel Rodrigue2. She limped into Louisbourg harbour a shell of her former self, dismasted and carrying a desperate assortment of tattered worn-out canvas. During the crossing, the carpenter of L’Iphigénie had had to literally tie the hull of the ship together with cables in order to keep it from sinking. To make matters worse, her captain, a man by the name of Fremont was a completely incompetent navigator who had made so many poor decisions during the voyage that Johnstone had resigned himself to the fact that he would die on the open sea. When finally they put into Louisbourg harbour, the townspeople lined the entire quay to look at the dilapidated hulk that had just dropped anchor off of the town, amazed that a vessel in such as state as the Iphigénie was still afloat. Once the bitter crew had disembarked, Johnstone somehow managed to get his hands on a large piece of wood, a “cudgel”, and started beating Fremont to the cheers of his fellow soldiers right there on the quay. Fremont drew his sword in retaliation but ended up receiving a few good blows from Johnstone before Loppinot3, the town-major, broke up the scuffle and dispersed the crowd4. It was discovered later that the owner, Michel Rodrigue was in business with certain members of the Admiralty Court of Louisbourg, and was able to get them to declare the ship seaworthy despite the fact that it was taking on twelve feet of seawater an hour. Clearly, the Chevalier de Johnstone’s first impressions of Louisbourg, Île Royale and its inhabitants were far from stellar.

It’s no surprise that the Chevalier de Johnstone hated his time on Cape Breton Island – he wasn’t a fisherman, businessman or sailor, and with no prospect of a career in the French military there was nothing for him to do in Île Royale that was worth his while. When not on duty, he would go fishing with his servant in the streams and rivers up behind the harbour, then pour over historical and military commentaries in his spare time and finally when he needed a change of pace, he would garden5. His rations “consisted during the winter solely of cod-fish and hog’s lard, and during the summer, fresh fish, bad rancid salt butter, and bad oil.”6 “One does not see the sun sometimes for a month,”7 he says in his memoirs, something most Cape Bretoners can relate to no matter what century they are from. Although he “enjoyed a true and perfect satisfaction from the esteem and friendship of all [his] comrades,” he skillfully avoided getting involved in the rivalries that existed between the three large factions in the officer corp of Île Royale – local officers, officers from Canada and reformed officers from France – which was not an easy feat to achieve.8 He also benefitted greatly from the patronage of the Count de Raymond, Louisbourg’s governor from 1751-1753, even joining him on a tour of the island. He made note of the many “beautiful natural meadows”9 he saw along the way.

As early as 1750 there were rumblings of renewed hostilities in Nova Scotia10, and as the years went on it was clear that the frontier skirmishes of Acadia and the far interior would erupt into another full-scale confrontation between Great Britain and France in North America. Johnstone was preparing to leave his post in the Compagnie Franche11, but with the current situation in Nova Scotia and Île Royale, he felt it would be wrong to leave at such a time. As war broke out and the North Atlantic became the backdrop for the British and French navy’s proverbial game of cat-and-mouse, the port of Louisbourg became a very, very busy place, serving as the layover for the French navy and French troops on their way to places like Québec, Montréal and the frontier.

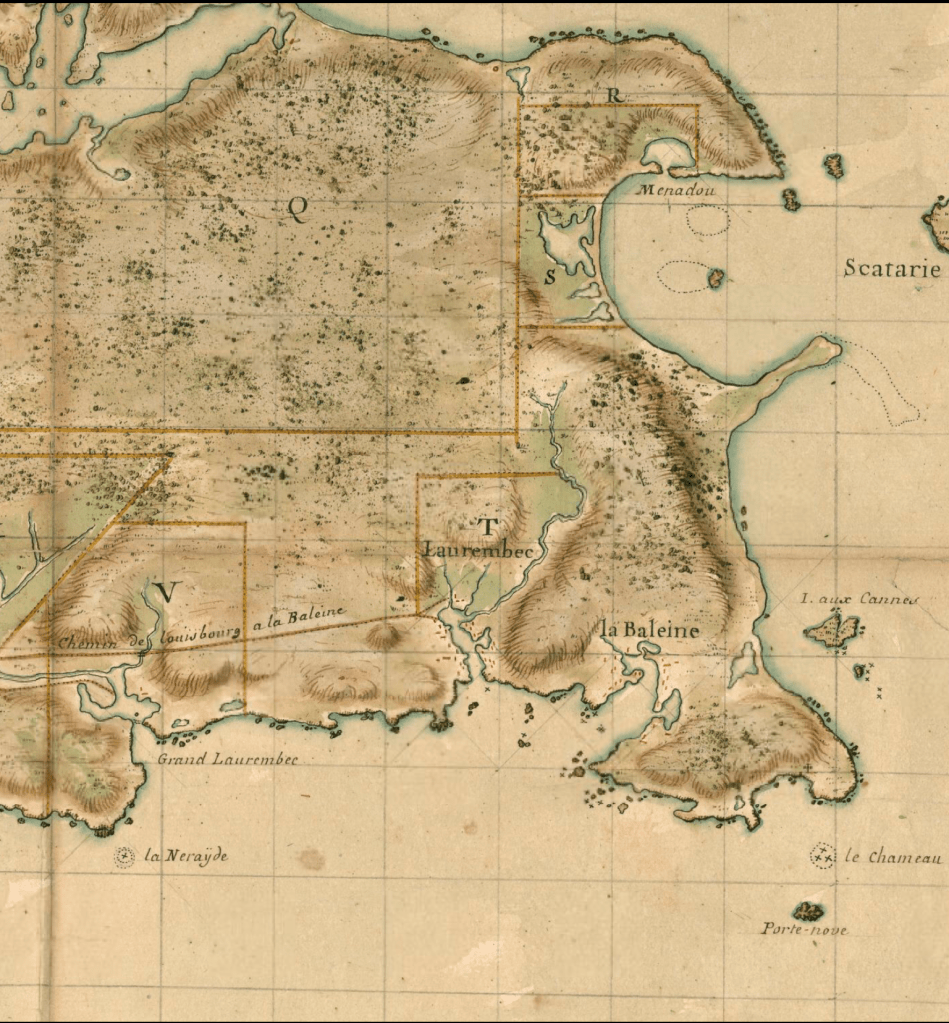

In 1756, word had reached Louisbourg that a French merchant ship had sought refuge in the harbour of Menadou (present-day Main-a-Dieu) after being chased by two British ships that were now sitting outside of the harbour trying to flush them out12. Immediately a detachment from Louisbourg was organized to go render assistance, and Johnstone was assigned to the task along with the Chevalier Duchambon, who commanded the operation. The Chevalier Duchambon came from one of the foremost families in Île Royale at the time, the Du Ponts, from Ste Anne’s13. His father was most likely the former governor of Île Royale, Louis Du Pont Duchambon. One of the sons of Duchambon was described as “mediocre in all respects,”14 and it seems the trait ran through the entire family.

With fifty soldiers, twenty artillerymen and eight cannons, the detachment set off for Menadou, probably taking le chemin de Louisbourg à La Baleine, one of the Island’s main thoroughfares which connected the outports of Grand Lorembec (Today’s Big Lorraine), Petit Lorembec (Little Lorraine) and La Baleine to Louisbourg. Still in use today and known as the Louisbourg Main-A-Dieu Road, it’s one of the oldest roads in Canada. This road brings you through a part of the island that saw much early activity – in 1629 the Scots built the short lived Fort Rosemar in the Baleine area15, only for it to be burnt to the ground by French captain Charles Daniel, and in 1725 when the ship Le Chameau struck the Porte-nove rocks and broke up along the coast, the dead were interred at Baleine.

When Johnstone and the Chevalier Duchambon arrived at Menadou, they immediately disagreed on how to proceed16. In the end Duchambon made the final call, and to defend the merchant ship now anchored deep within the harbour he decided to bring the entire detachment aboard. Johnstone was convinced that they would all be captured by the British in a matter of days, but to their surprise, the two British ships suddenly spread as much canvas as they could and sped off southwards. It was only an hour later that they understood why they had taken off so fast – a squadron of French ships, bearing down fast and steering for Louisbourg. Leading the squadron was Beaussier de l’Isle, a man known as an intrepid seaman, and sailing into Louisbourg, he took two-hundred volunteers from the town and headed off to give chase to the British ships, still visible on the horizon. Beaussier de l’Isle ended up fighting off two enemy ships at once for five or six hours, before having to give up the fight in order to keep his own ship, L’Héros, afloat – a battle in which he personally received recognition from Louis XV17.

The following year in 1757, while Louisbourg was at its busiest, a disturbing episode took place that no doubt would’ve deeply affected the Chevalier de Johnstone. While travelling to Île Royale aboard the Iphigénie, he became friends with two captains of the Compagnie Franche, the Chevalier de Montalembert and the Chevalier de Trion18. Not long after arriving in the colony, Montalembert married a young woman from Île Royale who eventually cheated on him with another man from the garrison. It became well known throughout the town, which lead to Montalembert having a nervous breakdown. One day he left the town to go hunting and disappeared down the Great Mira Road, or the grand chemin de Miré and never returned to Louisbourg. His friend the Chevalier de Trion was sent out to search for him and the Mi’kmaq helped by searching the woods throughout the shores of the Mira River, but no one was able to find him.19 It wasn’t until three months later that they found his body in a lake. Having faced death on the high seas alongside Montalembert, perhaps it was just too difficult for Johnstone to retell these events in his memoirs.

When it was clear that the British were readying an assault on the fortress, Johnstone volunteered to escort some hundred British prisoners from the Miramichi River to Québec. Intelligence from Nova Scotia had listed the regiments of Lee, Warburton and Lascelles20 as forming part of the British expedition leaving from Halifax in the spring of 1758, all of which had been the Jacobites’ prisoners 13 years earlier at the Battle of Prestonpans in Scotland. He had no interest of being identified and perhaps even hanged for his participation in the Jacobite Uprising were Louisbourg to fall to the British, so he left his belongings behind save a couple shirts stuffed into his pockets and sailed away for Acadia, finally liberated from his purgatory.

Upon arriving in Québec, he was immediately appointed aide-de-camp of the Duc de Lévis, and soon after to the Marquis de Montcalm, the commander-in-chief of the French army in North America. He was present for the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, Île aux Noix and finally the surrender of Montréal, which closed the chapter of French rule in Canada. After fourteen years on the run, it was in Montréal that the British finally tracked him down. But in the end the British officials turned a blind eye to his identity, allowing him to lodge with a relative of his that was serving in the British Army while he awaited transportation back to France with the other regiments of the French army.

The Chevalier de Johnstone lived the rest of his life in France, returning to Scotland only once to care for some personal matters. His time in Louisbourg was never anything more than a layover during his exile from Scotland, but he nevertheless provides through his memoirs a fleeting glimpse into events and individuals that are missing from Cape Breton’s cultural memory today. From his duel on the quay to his fruitless endeavours in Menadou, Johnstone’s memoirs recreate a living, breathing society and provide details of events that form the basis of a regional folklore that did not have the time to develop. One can only wonder what he would’ve thought had he been told that much of the population of Cape Breton Island would one day hail from his own native soil.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Johnstone, J. Johnstone., Winchester, C. (187071). Memoirs of the Chevalier de Johnstone vol. II p. 168 Aberdeen: D. Wyllie & son

- Michel Rodrigue’s property was reconstructed for the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site

- Loppinot’s property was reconstructed for the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site

- Johnstone, J. Johnstone., Winchester, C. (187071). Memoirs of the Chevalier de Johnstone vol. II p. 169 Aberdeen: D. Wyllie & son

- Johnstone, J. Johnstone., Winchester, C. (187071). Memoirs of the Chevalier de Johnstone vol. II p. 179 Aberdeen: D. Wyllie & son

- Johnstone, J. Johnstone., Winchester, C. (187071). Memoirs of the Chevalier de Johnstone vol. II p. 172 Aberdeen: D. Wyllie & son

- Johnstone, J. Johnstone., Winchester, C. (187071). Memoirs of the Chevalier de Johnstone vol. II p. 178 Aberdeen: D. Wyllie & son

- Johnstone, J. Johnstone., Winchester, C. (187071). Memoirs of the Chevalier de Johnstone vol. II p. 179 Aberdeen: D. Wyllie & son

- The Campaign of Louisbourg 1750-’58, Chevalier de Johnstone, p. 9-12

- The Campaign of Louisbourg 1750-’58, Chevalier de Johnstone, p. 4

- Johnstone, J. Johnstone., Winchester, C. (187071). Memoirs of the Chevalier de Johnstone vol. II p. 181 Aberdeen: D. Wyllie & son

- The Campaign of Louisbourg 1750-’58, Chevalier de Johnstone, p. 8

- Ægidius Fauteux, Les Du Ponts de l’Acadie. Bulletin des Recherches Historiques, September 1940, p.261

- Ægidius Fauteux, Les Du Ponts de l’Acadie. Bulletin des Recherches Historiques, August and September 1940

- C. Bruce Fergusson, “STEWART, JAMES, 4th Lord Ochiltree,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed June 24, 2021, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/stewart_james_1E.html.

- The Campaign of Louisbourg 1750-’58, Chevalier de Johnstone, p. 9

- The Campaign of Louisbourg 1750-’58, Chevalier de Johnstone, p. 11

- Johnstone, J. Johnstone., Winchester, C. (187071). Memoirs of the Chevalier de Johnstone vol. II p. 156 Aberdeen: D. Wyllie & son

- “Les derniers jours de l’Acadie (1748 – 1758)”, Gaston du Boscq de Beaumont, p.213-215

- Johnstone, J. Johnstone., Winchester, C. (187071). Memoirs of the Chevalier de Johnstone vol. II p. 181 Aberdeen: D. Wyllie & son