(October 7, 2022 – Since the publishing of this article, historian Éva Guillorel from the University of Rennes in France has done significant research into the origins of “La Complainte de Louisbourg.” She has uncovered evidence that this Acadian folksong is based on an older French song written about one of the sieges of Philippsburg. Her findings were published in the Spring 2022 edition of the journal Acadiensis and updates some of the information found in the article below.)

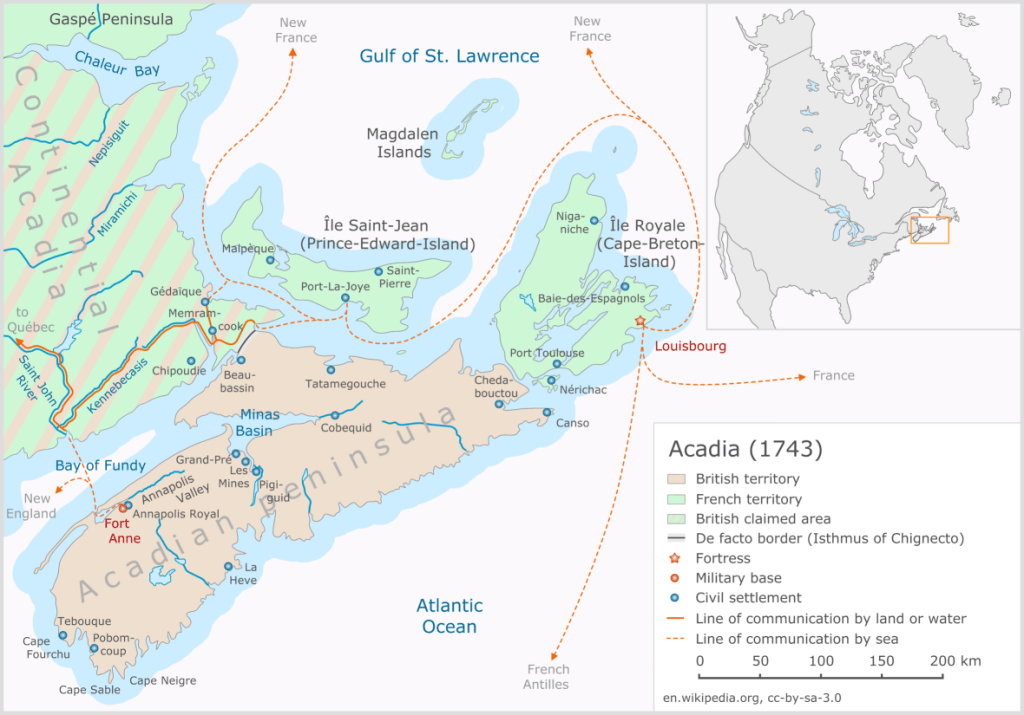

During the first half of the 18th century, the fault-line between the colonial empires of Great Britain and France ran through Canada’s Maritime region – the modern day provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. During those years, these borderlands existed in an almost continuous state of unrest, frequently erupting in skirmishes, raids and clashes regardless of if it was a time of war or not. At the end of each officially declared war that touched the Maritimes, the French would lose another piece of their traditional colonial claims – first mainland Nova Scotia was ceded to the British in 1713, followed by the occupation of Île Royale and Île Saint-Jean in 1758, then finally New France in its entirety in 1763. Chaos ensued in the wake of those receding borders, and the Acadians were caught in the middle of it.

In the years following their expulsion at the hands of the British, the Acadians made their way back to the only home they had ever known. Some of them settled in the regions that their families had previously come from before their expulsion, while others decided to forge new realities. The area now known as Chéticamp, on the northwest coast of Cape Breton Island was settled during this time, beginning in the year 1782. The location of Chéticamp is telling – wedged between the Cape Breton Highlands on one side and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence on the other, these were clearly a group of people who wanted to be left alone – far from any potential future fault-line. The Island, though now an extremely peaceful area, had been a battleground for the French and English during the 1740’s and 1750’s, and then an offshore battleground for the American, French and British navies in the 1770’s and 1780’s. The location of their new settlement ensured that whatever changes might come upon Cape Breton Island in the future, their area would not be involved.

Today, only a three hour drive separates the towns of Chéticamp and Louisbourg, and if one were to look at a map of Cape Breton Island they might make the assumption that their histories dovetailed nicely, that these places must be old familiar acquaintances. But nothing could be farther from the truth. In a historical sense, these two settlements are practically strangers to each other. By the time the first wave of settlers stepped onto the shores of Chéticamp, the only things left of the once magnificent town of Louisbourg was a handful of dilapidated houses standing in what used to be a busy intersection – and by 1782, inhabited by English families. The language spoken at Chéticamp was the French of Acadia, but at Louisbourg, it had been the French of France. And in the years leading up to the final disconnect between the Acadians and France, their relationship had grown stale.

But hidden within the vast catalogue of traditional songs from Chéticamp, we find “La Complainte de Louisbourg.” It is sung about the 1745 siege of Louisbourg from the standpoint of Governor Louis Du Pont Duchambon. Its lyrics are incredibly detailed, including vivid descriptions that could only have been provided by an eyewitness to those events. It even goes so far as to list the precise honours of war afforded to the French garrison in the final terms of surrender. Despite there being many Acadian communities on Cape Breton Island today (such as those on Isle Madame) whose history actually does overlap with that of Louisbourg’s, this lament seems to have originated solely with the Acadians from the region of Chéticamp. It leads us to ask, how did this information find its way into Chéticamp’s folklore?

Despite there being many Acadian communities on Cape Breton Island whose history overlaps with that of Louisbourg’s, “La Complainte de Louisbourg” seems to have originated with the Acadians of Chéticamp

At least two direct links1 exist between the towns of Chéticamp and Louisbourg – Jeanne Dugas and Joseph Gaudet, some of the very first settlers to the Chéticamp area.

Jeanne Dugas was born in Louisbourg the 16th of October 17312 to an Acadian family originally from Grand Pré, Nova Scotia. Historian Anne Marie Lane-Jonah says the following about Jeanne’s upbringing: “Jeanne lived in the cosmopolitan port town of Louisbourg until she was about 10-12 years old. Her family moved back to mainland Nova Scotia/Acadia, possibly to avoid the coming strife as war approached in the mid-1740s; this move began what would be for Dugas a lifetime of peregrinations that took in the entire Maritime region: avoiding war, fleeing expulsion, being captured and imprisoned, resettling, and then re-resettling again. The journey for Jeanne and her husband, Pierre Bois, ended more than 40 years later, in 1785, when they were among “les quatorze vieux” – the founders at the Acadian village of Chéticamp in western Cape Breton.”3

Her older brother, Joseph Dugas, experienced much of the same hardships throughout his life. Born in Grand Pré, Nova Scotia in 1714, he was an eye-witness to many of the pivotal moments in the history of the Maritimes. After living in Île Royale for almost three decades, he fled to Québec after the final surrender of Louisbourg in 1758, was imprisoned in Halifax in 1761, settled in St. Pierre et Miquelon after his release and then was finally deported to St. Malo, France in 1778, only to pass away within a few months of arriving. The lives of both Joseph and his sister Jeanne typify the reality of what life was like on the Acadian frontier in the 18th century.

Joseph Dugas was an extremely active figure in Louisbourg’s commercial life throughout his three decades in Île Royale. At age 15 he was the captain of a small merchant ship, and then along with his father he supplied the garrison of Louisbourg with firewood. Historian Bernard Pothier, speaking about this contract, says: “Between 1730 and 1737 the annual income from this business averaged 5,567 livres, phenomenal earnings compared with a garrison captain’s pay of 1,080 livres.”4 Industrious and capable, it would be an understatement to say he was doing well for himself in the young colony. After these commercial successes, Dugas became involved with two other prominent Louisbourg merchants and together supplied the town with beef, driving the cattle overland across the isthmus of Chignecto himself and then bringing them to Louisbourg by boat. This afforded him a unique view of what was transpiring in Nova Scotia during the years leading up to the declaration of war between Great Britain and France, and his abilities and circumstances did not go unnoticed by the authorities. Joseph was soon enlisted by the French government in Île Royale to carry information back and forth to French assets on the mainland. On the 16th of May 17455, with the New England troops already digging into the hills above Louisbourg harbour, Governor Duchambon tasked Dugas with the urgent mission of travelling to Nova Scotia and locating Paul Marin de La Malgue and his Canadian and Mi’kmaq troops in order for them to come to Louisbourg’s assistance. Although it’s unclear if Dugas was able to return to Louisbourg before its surrender on June 286, when he did eventually return, William Pepperrell, commander-in-chief of the New England forces occupying Louisbourg and Commodore Peter Warren used him in much the same capacity as did Governor Duchambon. The 1752 census tells us that Joseph Dugas was reunited with his sister Jeanne and her husband Pierre Bois in Port Toulouse (present-day St. Peter’s, Nova Scotia)7 after Île Royale was returned to the French at the end of the war.

Looking at his close involvement with the French and English governments at Louisbourg right before and directly after its capture, it is possible that Joseph Dugas was the eye-witness that breathed life into “La Complainte de Louisbourg”, providing details of the siege of 1745 to his sister Jeanne and her husband Pierre. In turn they would have taken that information through their sojourns and finally to Chéticamp, where they made their final home in the 1780’s.

Two strong links exist between Chéticamp and Louisbourg: Jeanne Dugas and Joseph Gaudet

Another link exists between Chéticamp and Louisbourg with the family of Joseph Gaudet, one of the “Quatorze Vieux” that petitioned the government of Cape Breton for land grants in 1790. The 1818 census of Chéticamp8 reveals that two of Joseph Gaudet’s sons, Maximilien and Louis were born in Louisbourg about 1761 and 1769 respectively. As to how long the family was actually living in Louisbourg during its final years as a town is unclear, and I would be very interested in knowing more about this part of their story, were anyone to have this information. Although Joseph Gaudet was born in Nova Scotia around 1743, making him around 2 years old at the time of the first siege, it’s possible that once he married and moved to Louisbourg, he obtained enough of the story of the first siege to piece together what had happened and brought that information with him to Chéticamp later in life.

Although the story of how “La Complainte de Louisbourg” came to be is still unknown, two very strong possibilities exist as to how the information contained in its verses arrived in the quiet, idyllic region of Chéticamp, Nova Scotia: firstly, Jeanne Dugas and her husband Pierre Bois, and secondly the family of Joseph Gaudet. Perhaps its source of information is this illusive eye-witness to the long lost Colony of Île Royale, or perhaps it is the product of this eye-witness’s grandchildren or great-grandchildren preserving their ancestor’s words in song. It may very well be that at a future time the entire story of this song will finally come to light.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Due to the tumultuous nature of those decades, there were many things that went undocumented. More family connections between Louisbourg and Chéticamp undoubtedly exist but have been lost to time.

2 Louisbourg Parish Records – G1, Vol. 406, Registry 4, f. 31v – http://www.krausehouse.ca/krause/ParishRecordsHtml/Default.htm

3 Lane-Jonah, A. M. (2016). Everywoman’s Biography: The Stories of Marie Marguerite Rose and Jeanne Dugas at Louisbourg. Acadiensis, 45(1). Retrieved from https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/Acadiensis/article/view/24584

4 Bernard Pothier, “DUGAS, JOSEPH (1714-79),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 3, 2021, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dugas_joseph_1714_79_4E.html.

5 Letter from Duchambon to Maurepas, September 2 1745

6 In Duchambon’s letter to Maurepas dated September 2 1745, Duchambon reveals what took place in Nova Scotia when Marin received his letter (which had been entrusted to Dugas) about June 3rd (according to George Rawlyk). It’s possible that Dugas made it back to Louisbourg before the French surrendered on June 28 and conveyed this information to Duchambon, but Duchambon does not specify.

7 1752 Census of Île Royale and Île St-Jean, Sieur de la Roque – “Port Toulouse”

8 Commissioner of Public Records Nova Scotia Archives RG 1 vol. 445 no. 47 – https://archives.novascotia.ca/census/RG1v445/returns/?ID=3638